Click here to download a PDF copy of the report.

Highlights

- Based on our analysis of ED survey data from academic year 2007-08 to 2015-16:

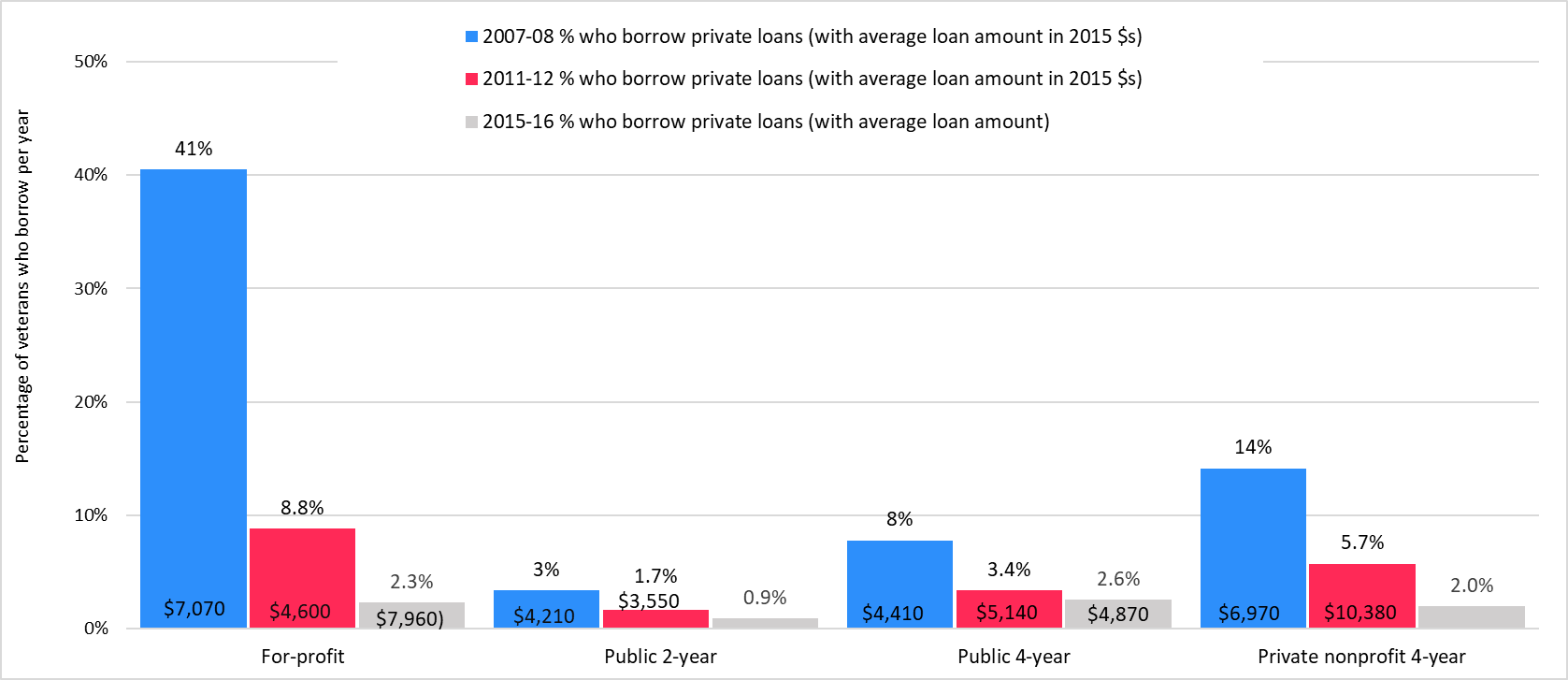

- The proportion of undergraduate student veterans at for-profit schools taking out private student loans dropped by almost 95 percent (see fig. 1).

- Although the proportion of undergraduate student veterans with private student loans in the public and nonprofit sectors also declined, a significantly lower percentage had such loans in academic year 2007-08 (see fig. 1).

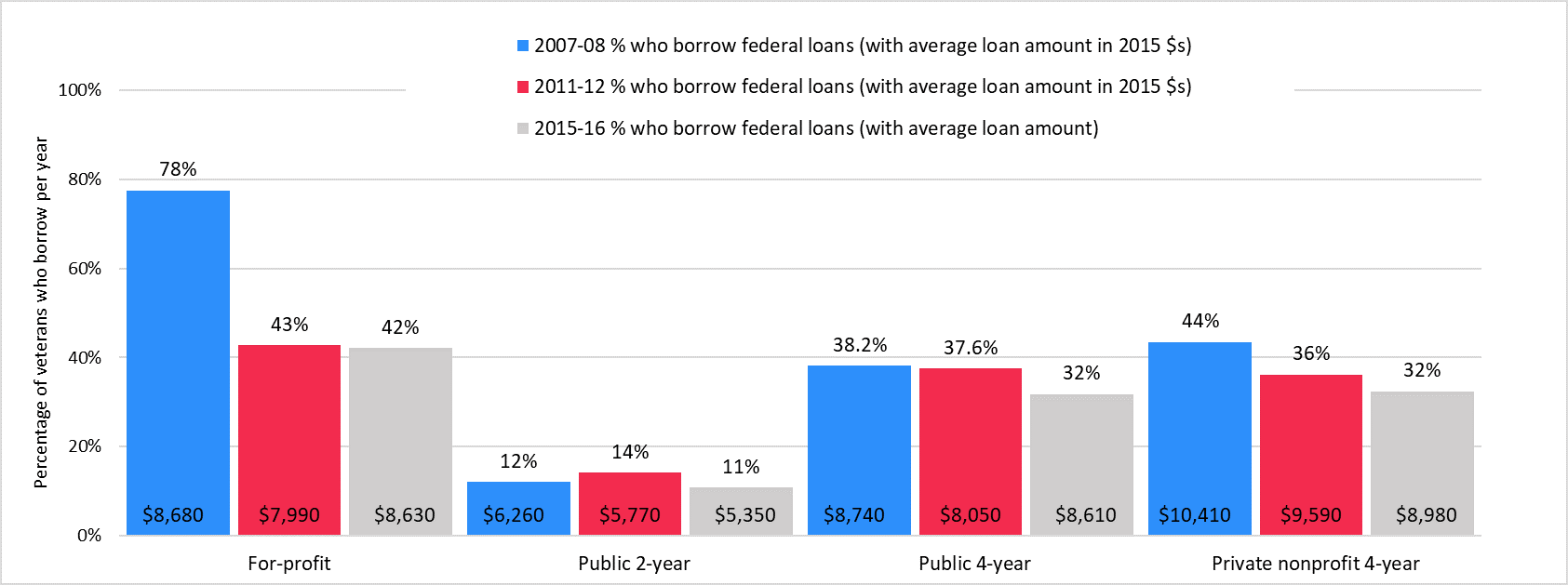

- The proportion of veterans with federal student loans across all institutional sectors also declined (see fig. 2).

- In 2014, CFPB filed lawsuits alleging that Corinthian and ITT used in-house private student loans to circumvent the statutory requirement that caps for-profit school revenue from federal student aid at 90 percent. Although both schools declared bankruptcy, the CFPB reached settlements with companies that had helped the schools manage those loans.

- Private student loans are susceptible to violations of the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act (SCRA). For example, loan servicers who failed to reduce the interest rate on federal and private student loans originated prior to active-duty service agreed to provide refunds totaling $60 million to 77,000 servicemembers.

- In 2012, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), reported that many borrowers (1) did not know that they had fewer options repaying private vs. federal student loans, and (2) took out private student loans even though they were still eligible for federal loans. Similarly, a 2019 report by The Institute for College Access & Success (TICAS) found that less than half of the 1.1 million undergraduates who took out private student loans in 2015-16 borrowed the maximum amount of the more affordable federal loans.

Despite the generosity of the Post-9/11 GI Bill, student veterans may need to take out loans, including private student loans. Veterans may borrow because they: (1) do not qualify for the full benefit, which requires 36 months of active duty service after September 10, 2001; (2) find the Post-9/11 living stipend insufficient, particularly for veterans with dependents, (3) are enrolled part-time or are taking too few courses, which reduces the amount of the benefit; (4) may have already exhausted their 36 months of GI Bill benefits; (5) are using the Montgomery GI Bill, which is less generous than the Post-9/11 benefit; or (6) are enrolled in an exclusively online degree program and therefore receive a reduced living stipend.

What Is the Difference Between Private and Federal Student Loans?

Private student loans are defined as any loans not originated by the U.S. Department of Education (ED), which administers the federal student aid program. Private student loans can have higher interest rates because they are based on a borrower’s credit score and may lack other protections available with federal student loans. Private student loans are available from a variety of sources, including banks, credit unions, and other financial institutions; some schools; and, state-based or affiliated entities. Estimated private student loans for academic year 2018-19 totaled $9.66 billion. In contrast, federal student loans totaled about $93 billion during the same academic year. According to a private student loan consortium, private loans account for an estimated 8 percent ($125 billion) of the $1.6 trillion in student loan debt as of June 2019, with federal student loans representing the bulk of such debt.[1]

Students taking out private loans undergo a credit check, frequently require a cosigner, and may face variable interest rates that are dependent on market conditions. In contrast, for federal student loans, a borrower’s credit history is not examined, the loan amount is based on demonstrated financial need, and the interest rate is fixed for the life of the loan. As of April 2019, the interest rate on private student loans was as high as 14.2 percent. In contrast, the rate for federal student loans was 5.05 percent. Neither federal nor private student loans are dischargeable in bankruptcy unless the borrower can prove that repayment causes “undue hardship.”[2]

In addition to lower interest rates, federal loans offer a variety of repayment options that help borrowers cope with employment challenges that may affect their ability to repay, including income-driven repayment, public student loan forgiveness, forbearance, and deferment. Forbearance and deferment allow borrowers to temporarily suspend their payments. Interest still accrues on certain federal student loans while payments are suspended and the period of suspension doesn’t count towards loan forgiveness; as a result, ED recommends that borrowers consider income-driven repayment plans. Such plans base student loan payments on income and family size.

Similar payment options may not be available from private lenders and the variability in private lenders’ requirements and payment options present a challenging landscape for individual borrowers. For example, private loans from the state-affiliated New Jersey Higher Education Assistance Authority have no income-driven payment options and are not dischargeable at death.[3] In contrast, private loans from the Massachusetts Educational Financing Authority provide deferred payments until after graduation, offer lower interest rates with a cosigner, and release the cosigners from responsibility for the loan after 48 consecutive payments.[4]

Our Research Findings on Veterans’ Private Student Loan Debt

We analyzed ED survey data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) to evaluate the impact of the more generous Post-9/11 GI Bill on trends in student veteran borrowing of both federal and private student loans.[5] Our work has focused on undergraduate veterans and included both veterans using and not using GI Bill benefits.[6] Our analysis found that from academic year 2007-08 to 2015-16:

- The proportion of undergraduate student veterans at for-profit schools taking out private student loans declined dramatically from 41 percent to 2.3 percent during this 8-year period, correlated with the introduction of the Post-9/11 GI Bill. However, average annual borrowing increased from about $7,000 to almost $8,000 (see fig. 1).

- In academic year 2015-16, veterans not using GI Bill benefits at a for-profit school were almost four times more likely to take out private student loans than those using benefits. [7]

- The proportion of undergraduate student veterans with private student loans in the public and nonprofit sectors also declined. Compared to for-profit schools, however, the proportion with such loans in these two sectors was significantly lower in academic year 2007-08, ranging from 3 percent to 14 percent (see fig. 1).

- The bulk of veterans’ private student loans were from financial institutions. In contrast, the proportion of private student loans from schools or state-based entities ranged from a low of 3 percent to a high of 4.7 percent from 2007-08 to 2015-16.

In general, the proportion of undergraduate student veterans taking out federal student loans also declined from academic year 2007-08 to 2015-16, with the largest drop at for-profit schools where borrowing declined from 78 percent to 42 percent (see fig. 2). In contrast, borrowing among other financially independent non-veteran students attending for-profit schools declined from 80 percent to 62 percent.[8] Overall, the generosity of the current Post-9/11 GI Bill is a factor in reducing the need to borrow for those veterans using their education benefits.

Figure 1: Percentage of Veterans Borrowing Private Loans and Average Annual Amount by Sector, 2007-08, 2011-12, and 2015-16

Source: NPSAS:08,12,16.

Note: The data represent the average amount borrowed in a single academic year. The 2007-08 and 2011-12 average loan values are in 2015 dollars. Dollar values are rounded to the nearest $10. Sample sizes are too small to produce average loan amounts in the public 2-year and nonprofit sectors for 2015-16.

Figure 2: Percentage of Veterans Borrowing Federal Loans and Average Annual Amount by Sector, 2007-08, 2011-12, and 2015-16

Source: NPSAS: 08,12,16.

Note: The data represent average amount borrowed in a single academic year. Federal loans include subsidized and unsubsidized loans and Perkins loans. The 2007-08 and 2011-12 average loan values are in 2015 dollars and are rounded to the nearest $10. Prior to 2010, federal subsidized and unsubsidized loans known today as Stafford loans were provided through two programs—the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program or the Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP). Under the Direct Loan Program, the Department of Education made the loans directly to students, while under the FFELP program the Department guaranteed loans made by private entities such as banks. FFELP loans were discontinued in 2010 and, since then, Stafford loans have been referred to as Direct Loans. The Perkins Loan Program provides low interest loans to help needy students finance the costs of postsecondary education. Students attending one of the approximately 1,700 participating postsecondary institutions can obtain these loans from the school. The school’s revolving Perkins loan fund is replenished by ongoing activities, such as collections by the school on outstanding Perkins loans made by the school and reimbursements from the Department of Education for the cost of certain statutory loan cancellation provisions. The proportion of veterans with Perkins loans was less than 1 percent in all years reported.

Predatory Schools Used In-House Private Loans to Circumvent the 90/10 Rule

In 2014, the CFPB filed lawsuits alleging that both Corinthian and ITT had used private student loans to circumvent the statutory requirement that caps for-profit school revenue from federal student aid at 90 percent.

The Bureau’s lawsuit against Corinthian alleged that the school used misleading advertising to encourage students to enroll and deliberately inflated tuition to force students to take out private loans with interest rates two to five times higher than federal student loans. Corinthian then used illegal debt collection tactics to strong-arm students into paying back those loans while still in school.

In September 2015, the CFPB won a default judgement against Corinthian and the court found the school liable for more than $530 million. By then, however, Corinthian had been liquidated in court bankruptcy proceedings. In 2017, CFPB filed a complaint and proposed settlement against Aequitas Capital Management, Inc., and related entities for aiding Corinthian’s predatory lending scheme. It is not clear if the proposed settlement of $183.3 million in loan relief to about 44,000 students was ever approved.

Although the CFPB sued ITT Tech in 2014 over its predatory private student loan program, the school closed and filed for bankruptcy in 2016. ITT’s inflated costs created a tuition gap that it pressured students to fill with the school’s private student loans with an origination fee of 10 percent and interest rates as high as 16.25 percent. In June 2019, the Bureau reached an estimated $168 million settlement with a company that was set up to manage ITT Tech’s private student loans and ITT and its trustees agreed two months later to pay $60 million to settle the CFPB’s 2014 lawsuit.

In September 2016, the CFPB settled a lawsuit with Ashford University over private-student loans that cost more than advertised. Ashford agreed to discharge all such loans, provide refunds of over $23.5 million to the borrowers, and pay the Agency a $8 million civil penalty.

Private Student Loans Are Susceptible to Violations of SCRA

SCRA requires loan servicers to cap the interest rate at 6 percent on both federal and private student loans originated prior to active-duty service. The CFPB shared complaints from military borrowers who reported difficulty obtaining the SCRA interest rate reduction with the Department of Justice and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. In May 2014, three Sallie Mae-affiliated entities agreed to provide compensation totaling $60 million to more than 77,000 servicemembers who were eligible for but had not received the rate reduction. Veterans Education Success worked with such a servicemember who received a check for $12,500. The interest rate on this servicemember’s private student loans, which constituted the bulk of this individual’s student loan debt, was about 15 percent.

Reports Question Need for Private Student Loans, Suggest that “Redlining” May Occur, and Indicate that Private Student Loan Market Now Exceeds Other Consumer Financial Markets

A statutorily required report by the CFPB and ED and a 2019 report by TICAS suggest that students aren’t always aware of the differences between federal and private student loans.

- CFPB’s 2014 report found that the growth in private loans prior to the 2008 financial crisis was facilitated by lenders’ direct marketing to students, which reduced schools’ involvement and led to students’ borrowing more than necessary to finance their education. The CFPB also reported that many borrowers might not have clearly understood the differences between federal and private student loans and were struggling to repay their private student loans.

- TICAS’s 2019 report found that: (1) less than half of the 1.1 million undergraduates who took out private student loans in 2015-16 borrowed the maximum amount of the more affordable federal loans; and (2) students who attended more expensive nonprofit (12 percent), for-profit and public 4-year schools (7 percent) were more likely to take out private loans compared to those who attended inexpensive community colleges (1 percent). According to ED, however, degree programs at for-profit schools are generally more expensive than comparable programs at 4-year public institutions.

- A February 2020 report by the Student Borrower Protection Center (SBPC) found evidence that private lenders may be discriminating (“redlining”) against borrowers by charging higher interest rates based on the institutions they attend. For example, a hypothetical borrower attending a community college would pay $1,134 more for a $10,000 private loan than a similarly situated student attending a 4-year public college. The report called on Congress to enhance oversight and for federal and state regulators to act immediately to halt such abuses.

- An April 2020 report by SBPC focuses attention on the private student loan market, noting that it is now larger than pay day loans and past-due medical debt and only 18 percent smaller than personal loans. According to the SBPC report, “Growth in the private student lending space has accelerated just as the volume of new federal student loans has begun to decline. Annual federal student loan originations fell by more than 25 percent between the 2010-11 and 2018-19 academic years, while annual private student loan originations grew by almost 78 percent over the same period.”

Methodology

We conducted a literature review to identify available research and data on private student loans. In addition, we summarized our own research on veteran student loan debt, which used ED survey data from NPSAS. Although our prior research had focused on private student loans from financial institutions, we updated our analysis to include all private loans—those from financial institutions as well as state agencies. Additional details on the survey data and our analytical approach can be found here.

[1]There is no comprehensive database on private student loans comparable to the National Student Loan Data System maintained by ED. The amount of outstanding private student loan debt is an estimate as are trends in private loan debt over time. For example, Measure One’s $125 billion estimate is based on voluntary reporting by a consortium of private student loan lenders comprised of the 6 largest financial institutions that originate such loans and 11 other lenders such as state-affiliated entities. According to Measure One, these lenders represented about 62 percent of outstanding private student loans. The CFPB reported that private student loans peaked in 2008 at $20 billion and contracted to $6 billion by 2011 but the College Board reported that private student loans peaked at $24.3 billion in 2007-08 and decreased to $7.9 billion by 2010-11. See table 1, pg. 10 at this link. Baum, Sandy and Kathy Payea. Trends in Student Aid 2011. Washington, D.C.: The College Board.

[2]See pg. 10 of hyperlink. In 2015, the Obama administration proposed making it easier to discharge private student loans if they didn’t offer flexible repayment plans. No action was taken on the proposal.

[3]The New Jersey Authority is a state agency with the sole mission of providing students and families with the financial and informational resources needed to pursue their education beyond high school.

[4]The Massachusetts Authority is a not-for-profit, state-based, and self-funded state-chartered student loan organization that helps families cover educational expenses.

[5]Our January 2019 report examined trends in student veteran borrowing from academic year 2007-08 through 2015-16, focusing on loans from financial institutions because the vast majority of veterans who take out private student loans do so from such entities. For this report, we updated our analysis to include private student loans from non-financial institutions, which had a minimal impact on the overall percentage of private loans.

[6]ED’s data includes all veterans surveyed, even those who may have been eligible but were not using GI Bill benefits. From the available data, it’s not possible to determine why veterans are not using GI Bill educational benefits. As a result, our analysis of NPSAS survey data includes all veterans, irrespective of their GI Bill status.

[7]According to ED survey data from 2015-16, similar proportions of undergraduate veterans are receiving (53 percent) or not receiving (47 percent) any GI Bill benefits. The difference in annual borrowing among undergraduate veterans using and not using GI Bill benefits in academic year 2015-16 was $200—smaller than might be expected given the high proportion of veterans not using GI Bill benefits. See our October 2019 report.

[8]See fig. 7 here. Veterans more closely resemble older students, rather than individuals who enroll in college right after high school. As a result, when comparing veteran and non-veteran students, we report on non-veteran independent students who are not reliant on their parents for financial support.

Vets_Ed_Success_Private_Student_Loan_Report_2020