OUR WRITTEN TESTIMONY FOR THE RECORD

LEGISLATIVE PRIORITIES SUBMITTED TO THE

SENATE AND HOUSE COMMITTEES ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS

119TH CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

February 25th, 2025

Chairmen Moran and Bost, Ranking Members Blumenthal and Takano, and Members of the Committees on Veterans’ Affairs:

We thank you for the opportunity to share our legislative priorities for consideration in the first session of the 119th Congress. Veterans Education Success works on a bipartisan basis to advance higher education success for veterans, service members, and military families, and to protect the integrity and promise of the GI Bill® and other federal postsecondary education programs.

We would like to praise the bipartisan efforts of your Committees, which led to several crucial successes last year. Your strong focus on oversight and accountability was essential and remains paramount in the new Congress. We would like to note several outstanding priorities we hope to see completed by the 119th Congress, including the Student Veteran Benefit Restoration Act, the Guard and Reserve GI Bill Parity Act, and legislation enacting more substantial quality standards.

We also understand the strong interest of this Congress to decrease overall costs. Therefore, we also highlight policy changes that offer significant cost savings. Today, we offer our full testimony for your consideration, outlining our top legislative priorities for this year. We propose the following topics and recommendations for consideration, which are discussed in detail in the pages that follow:

- Require minimum standards for GI Bill Programs – to protect veterans and stop waste, fraud, and abuse of taxpayer funds

- Restore VA education benefits when there is evidence of fraud

- Improve critical economic opportunity provisions of the Dole Act

- Mandate interagency data sharing as it relates to federal education benefits

- Improve the GI Bill Comparison Tool

- Oppose full housing allowance for online-only students – a costly and dangerous proposal

- Change VA’s debt collection practices against student veterans

- Forbid transcript withholding

- Ensure orderly processes and restoration of benefits in cases of school closures

- Strengthen Veteran Readiness & Employment

- Pass the Guard and Reserve GI Bill Parity Act so every day of service counts

We look forward to working closely with you and your staff members on these issues, and we thank you for the invitation to provide our perspective on these pressing topics.

1. Require minimum standards for GI Bill Programs – to protect veterans and stop waste, fraud, and abuse of taxpayer funds

Veterans count on the GI Bill to facilitate a smooth transition from military service to a successful civilian career. Veterans actively rely on VA’s program eligibility as a “stamp of approval” that identifies quality programs. Both veterans and taxpayers are entitled to a reasonable return on investment for the GI Bill.

Unfortunately, too many approved programs fail to educate veterans effectively or prepare them for a lifetime of success. Worse yet, many of these school programs cause serious harm to the veterans they are meant to help, leaving veterans with worthless credits, burdensome debts, and wasted benefits. Despite providing poor results, many of these programs and schools continue to rake in millions of taxpayer dollars through the recruitment and exploitation of veterans and the abuse of their hard-earned GI Bill benefits.

Wasting taxpayer funds on subpar education programs is preventable.

As we’ve previously reported, some of the lowest-quality schools receive the most GI Bill funding. Our research found that, from 2009 to 2017, eight of the 10 schools receiving the most Post-9/11 GI Bill funds accounted for 20% of all GI Bill payments, amounting to $34.7 billion.[1] Even more concerning, seven of these 10 schools had high numbers of student complaints and had faced state and federal law enforcement actions regarding allegations of deceptive advertising, predatory recruiting, and fraudulent loan schemes.[2]

Additionally, seven of these 10 colleges receiving the most GI Bill funds also spent less than one-third of the tuition they charged VA in 2017 actually educating the veterans, and they struggled with outcomes: Less than 28% of their students completed a degree, and only half earned more than a high school graduate.[3]

Additionally, approximately 100 colleges could arguably be accused of waste and fraud because they spent less than 20% of the tuition they charged VA on education costs for the veterans. These 107 colleges charged VA a total of $703 million in GI Bill tuition and fees in 2017, alone, but siphoned off $562 million in GI Bill money for non-instructional costs or overhead, including private jets and fancy cars for their executives. Predictably, they also have abysmal student outcomes.

In other words, bad actors are wasting GI Bill funding and defrauding VA and veterans.[4] This is preventable. There are thousands of excellent colleges in America, and very few bad actors.

Veterans we serve commonly express anger that VA would approve schools known for producing poor outcomes or that are under a law enforcement cloud. Veterans should never have to wonder why obvious scams like FastTrain College and Retail Ready Career Center were approved in the first place.[5], [6] Both schools proved to be a significant waste of taxpayer money, even before the FBI stepped in.

In the case of FastTrain College, the school was raided by the FBI and ordered to pay over $20 million for “having defrauded the U.S. Department of Education (ED) by submitting falsified documents to obtain federal student aid funds in connection with ineligible students.”[7], [8]

Even worse, “Retail Ready Career Center” ran a scam offering a 6-week HVAC training for veterans while also subjecting them to abusive practices, including taking their housing allowance and making them live in a substandard [disgusting] motel.[9] The owner falsely claimed, “We have the highest success rate of any other GI Bill program out there,” but the FBI and DOJ found differently.[10]

The owner of Retail Ready was eventually sentenced to more than 19 years in jail and ordered to forfeit $72 million of VA benefits to the federal government for lying to gain approval to enroll veterans; DOJ eventually recouped more than $150 million from the school.[11] According to DOJ, the owner had spent veterans’ GI Bill funds on a Lamborghini, a Ferrari, a Bentley, two Mercedes Benzes, a BMW, and real estate worth $2.5 million, among other purchases.[12]

Sadly, these are not isolated occurrences. In a similar incident in 2020, the owner of “Blue Star Learning” was sent to prison for 45 months and ordered to repay VA $30 million for his fraudulent GI Bill program with falsified job placements.[13]

As recently as 2022, the California Technical Academy was exposed for a scheme that involved over $100 million, the most significant case of GI Bill fraud prosecuted by DOJ.[14], [15] Unfortunately, so many predatory actors continue to reap the benefits veterans earned.[16]

Just last month, the VA OIG announced charges against an “owner of a non-college-degree school and its certifying official [who] conspired to submit fraudulent information to conceal the entity’s noncompliance with the rules and regulations of the Post-9/11 GI Bill program.” The report notes that over six years, VA paid more than $17.8 million to the program.[17]

The GI Bill program approval process must be strengthened to protect student veterans from low-quality and fraudulent schools. The statutes governing program approval are seriously outdated, even referencing classes taught “by radio,” and they continue to allow a low standard of entry.[18] It is time to update the statutes with minimum quality standards so that veterans can count on the VA’s “stamp of approval” as the indicator of quality they—and taxpayers—expect.

Complaints from student veterans attending GI Bill-approved programs continue to underscore the fact that subpar programs are failing to deliver (and we received 604 veteran complaints last year):

- Veteran DT: “I graduated from [my GI Bill-approved college] after 5 years, and in all that time, I never had a real-time conversation or interaction with a single teacher, not in a group or one-on-one. The way the courses were taught was totally ineffective. We would be assigned a bunch of stuff to read, and we were required to provide just two comments on an online discussion board. Occasionally, we were given assignments to complete, but the teachers never gave us feedback on the assignments.”[19]V

- Veteran AY: “Much of the curriculum was so outdated it might as well have been from the Stone Age. We were initially taught using the Unity and Visual Studios systems. Later, when the courses switched to modern programs … they did nothing to teach us how to use them. … I often was better off learning through tutoring, Google searches, and YouTube videos than I was following the actual instruction from its online courses. To make matters worse, the terminology and policies changed drastically from one class to another, creating confusion and hampering the learning experience. It was difficult to learn basic concepts and build upon them effectively.”

- Veteran AD: “I was accepted into the VRRAP program and set up to meet with [my GI Bill-approved college] to enroll in their Dental Hygiene program… Instructors are incompetent and inexperienced, Labs and course material are not taught, and I have to pay for a book payment plan for books costing 750 dollars that I can get on Amazon for less than 250 dollars. …. I was on the president’s list and dean’s list for the terms I have completed, but I haven’t even seen a dental dam or sterilized one piece of equipment. I am not learning any material and students are given answers to the quizzes and exams to keep them passing. Soon I have to let these students practice on me as part of the curriculum, but even our CPR AHA class was taught at a 22-student to 1-instructor ratio, so none of us are legally certified.”

- Veteran DD: “There are … issues such as the school replaying free web seminars as their own training and using unqualified people to lead the classes. They literally go to Youtube, find the free course by someone else, then they play that during the ZOOM meeting and call it training. Everything they are doing could have been done by me for free… They have also attempted on two occasions to place me in classes before I ever had the prerequisites to attend, they have me in classes that are not part of the program and do not serve a purpose except to show me in class…”

While the Veterans Auto and Education Improvement Act of 2022, codified as 38 U.S.C. § 3672A, creates a uniform application with some improvements to the approval standards, we urge the Committees to consider the following commonsense improvements to the Act:

- Expand the definition of adverse government action in 38 U.S.C. § 3672A(b)(1)(B) to all types of fraud, not just those relating to education quality that result in a fine of 5 percent of Title IV (a rarity). We believe Congress does not want a school or CEO that engaged in any other type of fraud – such as stealing federal student aid from Title IV, as Argosy University was accused of doing – to be in charge of GI Bill funds, yet that is what the statute currently allows.

- Extend to all education programs the requirements for minimum faculty credentials in § 3672A.

- Require schools to have adequate administrative capability to administer veterans’ benefits.[20]

- Require screening of a school’s financial stability before its approval to avoid sudden school closures. VA and SAAs appear to recognize in the risk-based survey SOP that they are not receiving sufficient financial records as part of the program approval process for unaccredited institutions.[21]

- Ensure that programs are not overcharging VA and that VA tuition funds are spent on veterans’ education. Our analysis found hundreds of GI Bill-approved programs that spend less than 20% on veterans’ education out of the tuition they are charging VA, and they – predictably – have abysmal outcomes.[22]

- Require a demonstrated track record of minimum student outcomes for a school to maintain Title 38 eligibility.

- Ensure school recruiters have the fiduciary responsibility to tell prospective students the truth. Today, it is standard practice at predatory schools to give recruiters–essentially sales representatives of the schools–deceptive titles like admissions “counselor” or “advisor.” The schools use high-pressure sales tactics to create false urgency about immediately enrolling prospects into programs that quickly burn through veterans’ GI Bill benefits and push them into borrowing significant amounts of student loans, often for programs of little or no value in the labor market. An essential step in ending these abusive practices would be to require all admissions and recruitment staff at eligible institutions to serve as fiduciaries with a duty of care toward the veterans they may be recruiting.

- In the case of online classes, require actual teaching, not pre-recorded classes. Many veterans tell us their online education consists of nothing more than watching YouTube videos, with no instructor engagement. YouTube videos are an inadequate substitute for regular and substantive interactions with qualified faculty and should not be funded with GI Bill dollars. The Committees should require “regular and substantive interaction” between virtual faculty and students.[23] Regular interaction with subject matter experts is essential to ensuring student veterans are receiving a worthwhile education.[24] Additionally, Congress should exclude asynchronous hours from the count of qualifying hours for clock-hour programs, and include minimum faculty-student interaction requirements–this would represent a significant cost savings to the overall program.

- Prevent schools from overcharging veterans for repackaged content. Some institutions charge excessive tuition for commercially available materials with little added value. In one case, a veteran paid $11,000 for a program that consisted of content available elsewhere for just $69. Congress should bar schools from inflating tuition costs for repackaged or freely accessible content at VA’s expense.[25]

Lastly, many schools are partnering with for-profit online program management (OPM) companies to offer numerous services, including academic instruction, even though reports expose poor student outcomes. The OPM loophole was created in 2011 by ED in direct contradiction to the statutory language of the Higher Education Act. It allows colleges to enter into revenue-sharing contracts with ineligible companies, which can then access federal dollars masquerading as the colleges with whom they share revenues.

Because VA relies on ED’s guidance, veterans have become a distinct target market for OPMs, who pitch shoddy online programs to them as a convenient solution for obtaining a degree while working. We encourage the Committees to direct VA to conduct oversight of the courses provided through OPM partnerships and to pass legislation requiring more thorough approval and oversight of all such courses and their recruiting practices.

Summary of recommendations:

- Strengthen the GI Bill program approval process to safeguard student veterans from ineffective and fraudulent schools by updating outdated statutes and adding minimum quality standards – at the same time, saving taxpayer funds from being wasted on obviously subpar education programs.

- Prevent bad actor colleges from siphoning GI Bill funds away from the veterans’ education and wasting them on overhead or unscrupulous costs.

- Extend requirements for minimum faculty credentials to all education programs and mandate adequate administrative capability for schools administering veterans benefits.

- Implement financial stability screening before approval to prevent sudden school closures and ensure responsible use of VA tuition funds.

- Require a demonstrated track record of meeting or exceeding defined student outcomes for Title 38 eligibility, require truthful recruiting practices, and prohibit overcharging VA.

- Address issues with online classes by requiring actual teaching, not pre-recorded sessions, and ensuring regular and substantive interaction between virtual faculty and students; exclude asynchronous hours from the count of qualifying hours for clock-hour programs; and include minimum faculty-student interaction requirements.

- Prohibit schools from overcharging veterans for repackaged or commercial, off-the-shelf content.

2. Restore VA education benefits when there is evidence of fraud

Several years ago, DOJ seized the bank accounts of the House of Prayer Christian Church – a purported “bible school” that we exposed and brought to VA’s attention, as veterans were being blatantly cheated out of their GI Bill and abused by an alleged cult leader.[26], [27]

In another example, DOJ recouped more than $150 million from Retail Ready Career Center and sent the owner, Jonathan Dean Davis, to jail for 19 years after he had swindled thousands of veterans, taking their GI Bill and their housing allowance but providing nothing of value in return.[28] But when the federal government recovered $150 million, the veterans did not get their GI Bill benefits back.

Even worse, veterans are sometimes the only students who are not made whole. For example, students with federal student loans from ITT Technical Institute have had their loans discharged due to the evidence of widespread fraud. Yet most student veterans who used their GI Bill to attend ITT Technical Institute cannot get their GI Bill benefits restored. The GI Bill statute currently allows restoration only for students who were enrolled at or near the time a school closes or loses program approval.

It is an absolute betrayal to student veterans that students have had their federal student loans discharged, but veterans cannot get back their GI Bill benefits. The fact that veterans are defrauded out of their hard-earned GI Bill is blatantly counter to Congress’ vision for the impact of the GI Bill.

Last year, the House passed H.R. 1767, the Student Veteran Benefit Restoration Act, by a nearly unanimous, highly bipartisan vote of 406-6. There is widespread agreement on the fundamental disparity of veterans being left out. We call on Congress to introduce and pass legislation that would finally provide veterans with a pathway to get their GI Bill benefits rightfully restored.

Summary of recommendations:

- Pass the Student Veteran Benefit Restoration Act.

3. Improve critical economic opportunity provisions of the Dole Act

We are grateful to Congress and the many advocates who helped make the Senator Elizabeth Dole 21st Century Veterans Healthcare and Benefits Improvement Act a reality.[29]

In particular, we strongly supported many of the economic opportunity provisions that addressed Fry Scholarship improvements (Sections 201, 202), more vigorous oversight of educational institutions and the introduction of risk-based improvements (Section 206), enhancements to the “rounding out” provision for full-time monthly housing allowances during a veteran’s final term (Section 208), electronic notification of Certificates of Eligibility to improve efficiency (Section 210), restoration of entitlement provisions to protect veterans’ benefits (Section 211), and expanded support for veterans attending foreign institutions (Section 214).

While we are grateful for these advancements, as detailed below, areas of concern warrant further discussion and potential modifications to ensure these laws fully serve the best interests of veterans and their families.

A. GI Bill Comparison Tool (Section 215)

We greatly support many of the GI Bill Comparison Tool enhancements, but this Congress must address crucial flaws that risk undermining their effectiveness and transparency. While provisions to retain data for six years and expand interagency collaboration are commendable, the process for handling student feedback raises concerns.

Section 215(c)(1)(A) amends 38 U.S.C. § 3698(b)(2)(A) to include that “if an institution of higher learning contests the accuracy of the feedback,” the school must be provided “the opportunity to challenge the inclusion of such data [in the Comparison Tool] with an official appointed by the Secretary.” Section 215 also provides that a school’s response to the feedback may be published. Presently, the Comparison Tool displays the number of student complaints filed against a school and the general topics of those complaints. However, it does not provide any details from the complaints themselves. VA does not publish the narratives submitted by student veterans.

With the enactment of Section 215, schools can contest a student’s complaint, thereby keeping prospective student veterans and the public from even knowing that complaints were made about the school. Even worse, bad actor schools will likely contest legitimate student complaints in order to hide the truth. Allowing institutions to contest even the inclusion of the fact of a student complaint serves only the interest of the institutions, not the veterans who took the risk of submitting a complaint to make their concerns known and not prospective student veterans who are considering which school to attend.

This provision of the new law will discourage student veterans from contacting VA with legitimate concerns. Already, veterans tell us that they feel VA does not have their backs because VA regularly “closes” veteran complaints about a school if a school responds – no matter what the school response actually says. This new law will lead veterans to fear being subjected to an administrative proceeding and to feel they will not have the resources to match the schools. Chilling veterans’ voices will deprive VA and the public of important information. Moreover, assuming a student veteran’s complaint survived such “accuracy” proceedings, Section 215 allows VA to publish the school’s response to the student’s complaint without providing student veterans the similar option to publish the details of their complaints. We call on Congress to adjust the law in the following ways:

- Do not allow institutions to challenge the inclusion of student veterans’ complaints in the publicly available data about a school.

- Give student veterans the option to publish the narrative portion of their complaints and to respond to a school’s claims about the veterans’ complaints.

- Require VA to include in the Comparison Tool whether the complaint was resolved to the student veteran’s satisfaction.

These changes would ensure the Comparison Tool serves its purpose of providing veterans with transparent information while holding schools accountable.

B. VET TEC Program (Section 212)

We support the short-term extension of the VET TEC Program, but believe modifications are necessary to address ongoing concerns. The program’s original intent—to provide veterans with rapid access to employment-focused training—has been affected by declining employment outcomes and incentives for participating schools.

The most problematic issue among the recent changes is a provision allowing providers to receive the final 50% payment from VA when students enroll in follow-on education rather than securing employment in their field of study.[30] This provision incentivizes schools to push veterans into additional programs rather than focusing on the program’s primary goal of securing meaningful employment.

Congress should eliminate enrollment in follow-on education as a qualifying criterion for the final payment. In alignment with the program’s intent, the final 50% payment should be tied to employment outcomes.

Further, we urge Congress to amend Section 212 to make clear that providers under the VET TEC Program are prohibited from seeking to recoup payments directly from veterans when VA determines it must withhold payments to the school because the school failed to meet the terms of the program, including that the veteran graduate and obtain employment. While Section 212 directs VA to give preference to a provider “that offers tuition reimbursement [to VA] for any student who graduates from such a program and does not find employment,” this provision does not go far enough to protect veterans.

Congress should make it plain that schools that wish to participate in VET TEC must never go after veterans for payments that VA deems unwarranted. Otherwise, some schools at risk of not receiving payment from VA will threaten to seek payment from veterans, and veterans could feel pressured into representing that they obtained employment just to avoid liability to the school.

This concern is not merely hypothetical. For example, according to records we received in response to a FOIA request, in January 2024[31], a preferred provider in the VET TEC Pilot Program sent a letter “threatening” to charge tuition and fees to a student veteran if the veteran did not find employment. Internal communications among VA staff indicate they were concerned that the provider may have sent similar letters to other veterans and that it appeared the student veteran was not receiving assistance in obtaining employment. VA staff seemed to think the VET TEC Pilot Program participation agreement prohibited the provider from collecting tuition and fees from student veterans. Still, the FOIA records do not disclose how VA ultimately concluded the issue.

Similarly, we were contacted by a veteran who graduated from a Veteran Rapid Retraining Assistance Program (VRRAP) program because his school was leading him to believe that, unless he had a job in the field, he would owe the school for the tuition payment withheld by VA[32] even though the VRRAP statute clearly provides that veterans do not owe any amounts to the school if they do not graduate or obtain employment.[33]

We recommend that Congress:

- Amend both VET TEC to clarify that a school will not be eligible to remain in the program if it attempts to recoup any payment from a veteran that is paid or would have been paid by VA if the school had met the conditions of the program, and, similarly, that a school will not remain eligible to remain in the program if it hides, or attempts to hide, the truth of a veteran’s failure to graduate or obtain actual employment, including by threatening financial repercussions to veterans who have not graduated or found employment.

- Enrollment in follow-on education should be eliminated as a qualifying criterion for the final payment. The final 50% payout should only be tied to employment outcomes aligned with the program’s intent.

- Require VA to include veterans service organizations in any advisory group established by the Secretary under Section 212.

These changes would restore the program’s focus on employment outcomes, as Congress originally intended and as should be expected from the reauthorized program.

C. Education institutions’ approval & participation in Title IV (Section 205)

We recommend that Congress modify 38 U.S.C. § 3675 to address unintended consequences of the new Dole Act. Specifically, the current language of Section 205 affects Section 1015 of the Isakson-Roe Act, which was designed to prevent colleges that lose Title IV approval from continuing to access GI Bill benefits. Recall that this affects only colleges offering a college education, and not job training programs.

Unanimous Committee leadership led to the unanimous enactment of Section 1015 of the Isakson-Roe Act, which sought to protect VA funds and taxpayer resources from waste at a college that had lost Title IV eligibility. Congress acted based on a specific real example of waste of taxpayer funds: Argosy University was cut off from Title IV programs after misappropriating Title IV funds, but VA officials stated that they had no way to protect GI Bill funds because the law prevented VA from acting based on an action under Title IV at another agency. Congress found it astonishing to see GI Bill funds continue to flow to a school that had been found to have stolen Title IV funds. Congress acted quickly to enact Section 1015 to protect student veterans from institutions that do not meet financial responsibility and administrative capability standards.

We believe the amended language in the new Dole Act of “(i) elects not to participate in such a program; (ii) cannot participate in such a program” fundamentally undermines the effectiveness of Section 1015 of the Isakson-Roe Act. We understand the impetus for this new provision of the Dole Act was to ensure that bible colleges that wish not to participate in Title IV are nevertheless eligible for GI Bill. We believe that was already solved by the existence of waivers by the Secretary of VA. Nevertheless, the solution enacted in the Dole Act goes too far because it functionally creates a significant loophole, enabling schools previously disqualified from Title IV for mishandling federal funds to regain access to GI Bill dollars. Our recommended changes include:

- Prohibit the VA Secretary from issuing waivers for institutions with a history of non-compliance with federal or state financial responsibility and administrative capability standards.

- Ensure any waivers are narrowly tailored and incorporate appropriate oversight and transparency mechanisms.

- Require VA to consult with independent accrediting bodies and the Department of Education before granting any waivers to ensure that a college offering college education is worthy of the GI Bill if the college is not eligible for (or seeks not to be eligible for) Title IV.

These changes would maintain the Secretary’s discretion while ensuring protections for student veterans and taxpayer dollars remain intact.

Summary of recommendations:

- On 38 U.S.C. § 3698(b)(2)(A), strike “if an institution of higher learning contests the accuracy of the feedback, the opportunity to challenge the inclusion of such data with an official appointed by the Secretary.”

- On the GI Bill Comparison Tool, extend the data retention period indefinitely, ensure anonymity and clear processes for veterans submitting feedback, and prioritize veterans’ input over institutional objections in disputes.

- On the VET TEC Program, eliminate “enrollment in follow-on education” as a qualifying criterion for final payment and clearly prohibit providers from seeking payment from veterans.

- On VET TEC, prohibit schools from going after veterans to recoup payments that VA refused to authorize after the programs failed to meet the program’s conditions.

- On Title IV eligibility, prohibit waivers for colleges with a history of non-compliance with federal or state standards and require VA to consult with independent accrediting bodies and the Department of Education before granting waivers.

4. Mandate interagency data sharing as it relates to federal education benefits

In 2012, Congress enacted a law requesting that VA seek information from other federal agencies (such as the Departments of Defense, Education, and Labor) to provide student veterans with information about student outcomes at colleges.[34] Thereafter, VA – with encouragement from your Committees – was supposed to enter into MOUs with other agencies to share data on student veterans. And, yet, little progress was made.

Our team embarked on a project to ensure that Congress’ wishes were heeded by the agencies. Specifically, we spent 8 years urging federal agencies to sign MOUs to share data. The results of that interagency data-sharing are the first-ever comprehensive understanding of the economic outcomes for enlisted veterans who use the Post-9/11 GI Bill.

This unprecedented interagency data-sharing enabled the first true analysis of the GI Bill.[35] The interagency research team was able to draw clear conclusions about veterans’ GI Bill outcomes by accounting for sociodemographic data as well as military rank, military occupation, service in hostile war zones, and academic preparation at the time of enlistment (by linking data from DOD).

We commend your Committees for requiring, in the Elizabeth Dole Act (section 215), VA to enter into an MOU with the U.S. Department of Education and the heads of other relevant federal agencies to obtain information on student veterans’ outcomes. The law states, “Such memorandum of understanding may include data sharing or computer matching agreements.”

However, given the history of VA’s not always completing what it is not explicitly required to complete, we urge the Committees to explicitly require VA to engage in interagency data-sharing. We also urge the Committees to expand this provision to require VA to enter into MOUs with the IRS, DOD, and the Census Bureau. Further, we urge the Committees to expand the requirement for data-sharing MOUs to cover veterans’ health outcomes as well, by collaborating with health-related agencies.

The recently published findings from the interagency GI Bill team demonstrate the impact of interagency data-sharing:

- By including data from the DOD’s testing of servicemembers’ academic preparation – through the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) – the research found that the higher the AFQT score, the more likely a veteran was to use their GI Bill, graduate from college, and have higher earnings.[36]

- By including demographic data from DOD and other agencies, the research showed that nearly 2 in 5 veterans did not use their GI Bill, often due to lack of information or financial barriers.[37] Nonuse was highest (82%) among those separating at ages 55-65, while those leaving at E-4 or with a 10-20% disability rating were most likely to use it. Many nonparticipants were unaware that transfers had to happen on active duty, while others delayed use to maximize benefits. Some found the housing allowance insufficient, and others struggled to secure VA home loans as lenders did not count GI Bill benefits as income.[38], [39]

- By including college completion data from the National Student Clearinghouse, the research showed that veterans’ college completion rate was double that of other financially independent students nationally[40] – but that veterans’ completion rate was 15% lower at four-year for-profit colleges than at four-year public colleges, even after controlling for veteran and military characteristics. It also found that veterans were less likely than non-veterans to attend public flagship universities even though veterans at public flagship universities were significantly more likely to graduate and were more likely to earn more money.[41]

- By including Census Bureau data on rurality, the interagency team found that veterans from rural and micropolitan areas were less likely to use the GI Bill.[42]

- By including earnings data from the IRS, the interagency team found that:

- Veterans who did not use their GI Bill were earning less, and the earnings gap was larger for female veterans, American Indian/Alaska Native veterans, and Black veterans.[43]

- Married veterans were more likely to complete a degree and earn more.[44]

- Veterans pursuing nondegree programs (such as certificate programs) and two-year degree programs (i.e., associate degrees) consistently earned less if they attended a for-profit program rather than a public program, even though for-profit programs consistently charged VA a higher tuition than public programs (and almost double the cost for Associates degrees).[45]

- Veterans’ earnings were higher when their college’s instructional spending was higher – and this was true across sex, race, rurality, and military rank, as well as overall among all veterans – yet only 1% of veterans attended colleges with the highest instructional spending.[46]

- Female veterans were significantly more likely than male veterans to use Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits and to earn a degree. Still, they earned significantly less than male veterans with the same degree. However, the earnings gap by sex was smaller for veterans than for the general population.[47]

- Racial and ethnic groups that have been historically underrepresented in higher education were more likely to use Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits to enroll in postsecondary education. Still, they were less likely to earn a degree within six years than veterans overall. Black veterans’ earnings were significantly lower than other veterans, and American Indian/Alaska Native earnings were also lower. Still, the earnings gaps for these racial subgroups were smaller for veterans than for the general population.[48]

This project demonstrates the type of information and insights that can be gleaned when agencies collaborate and share data.[49] Based on the richness of the project findings, and the broad policy implications, we strongly advocate for legislative measures that promote continued data-sharing efforts to achieve these data annually. We urge your Committees to enact a law requiring VA and VBA to share data on student outcomes with other agencies for the purpose of determining GI Bill outcomes.

We also urge your Committees to urge the other committees of jurisdiction to similarly require the agencies under their jurisdiction to share data on veterans’ outcomes. The Census Bureau is equipped to house and merge data from multiple agencies, as it did during the project we instigated. Ongoing data-sharing amongst agencies will enable a continued and holistic understanding of veterans’ educational experiences and outcomes.

We also recommend the establishment of an interagency task force focused on data collaboration efforts. This task force should be tasked with implementing a standard federal data dictionary associated with veterans, service members, and their families. It should define common data elements, following models such as the one proposed by the Bush Institute’s Veteran Wellness Alliance, and execute an annual crosswalk of Office of Postsecondary Education Identifiers (OPEID) and VA facility codes.[50] This standardized approach would streamline data collection and analysis, allowing for more effective collaboration and informed decision-making.

Summary of recommendations:

- Mandate that VA engage in comprehensive data-sharing with other agencies for the purpose of studying veterans’ outcomes – including health outcomes – and urge other Congressional committees of jurisdiction to require the agencies under their jurisdiction to share data about veterans with VA.[51]

- Establish an interagency task force focused on data collaboration efforts, including implementing a standard federal data dictionary associated with veterans, service members, and their families to define common data elements and a crosswalk of OPEIDs and VA facility codes.

5. Improve the GI Bill Comparison Tool

We urge the Committees to improve VA’s GI Bill Comparison Tool. Veterans need and deserve a modern college search tool. We appreciate the Committees’ prior work in requiring the tool to include side-by-side comparisons of schools and to search by geographic area. We also applaud many of the improvements to the Tool included in the Dole Act.

A. Prohibit Yelp-style reviews

We believe it essential to alert the Committees that VA has previously considered inviting veterans to post “Yelp”-style star ratings and reviews about schools. Such reviews are susceptible to unfair and deceptive manipulation by businesses. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has highlighted the well-documented and persistent problem of paid positive reviews and fake reviews because “[d]eceptive and manipulated reviews and endorsements cheat consumers looking for real feedback on a product or service and undercut honest businesses.”[52], [53] According to the FTC:

“Research shows that many consumers rely on reviews when they’re shopping for a product or service, and that fake reviews drive sales and tend to be associated with low-quality products. The rapid growth of online marketplaces and platforms has made it easier than ever for some companies to create and use fake reviews or endorsements to make themselves look better or their competitors look worse.”[54]

The FTC observed, “It can be difficult for anyone—including consumers, competitors, platforms, and researchers—to distinguish real from fake, giving bad actors big incentives to break the law.”[55] It is not hard to imagine the worst predatory schools finding ways to get fake reviews posted, including giving gift cards or other advantages to VA beneficiaries in exchange for posting positive reviews about the schools. Therefore, we strongly urge the Committees to require VA to officially abandon its idea of “Yelp”-style reviews.

B. Improve the Comparison Tool

We have the following important suggestions to strengthen the GI Bill Comparison Tool[56]:

- Risk Index. Establish a “Risk Index” to enable veterans to identify the riskiest schools. This would afford student veterans a precise measure of institutional risk, to make more informed enrollment decisions.

- Caution Flags. Improve the timeliness of Caution Flag updates so prospective students have access to warnings as soon as possible. Currently, VA fails to update and maintain Caution Flags accurately.

- Complaint Timeliness. Display student veteran complaints in a timely manner. Even after a complaint is closed, it can take several months to appear in the Comparison Tool, delaying critical information for prospective students.

- Full Complaint History. Show all student complaints received about a school on the Comparison Tool. When evaluating schools, veterans should have access to the full history, volume, and nature of complaints. SAAs, accreditors, federal agencies, and academic researchers would also benefit from knowing a school’s complaint history.[57]

- School Responses. Indicate whether a school responded to a complaint and whether the issue was resolved to the veteran’s satisfaction, following the Better Business Bureau model.[58] Veterans deserve to know if other veterans’ complaints were solved to their satisfaction and if their school responded.

- Closed Schools Data. Maintain historical records of schools that close or lose GI Bill approval in the “data download” section of the Comparison Tool. When schools disappear from WEAMS and the data archive, student veterans who may be entitled to GI Bill restoration struggle to find the necessary information.

- Complaint Transparency. Student veterans who submit a complaint through the Feedback Tool should be able to upload attachments and choose whether to make the narrative portion of their complaint public. Increased transparency helps students make better-informed decisions.

- Data Crosswalk. Automate the ED/VA data crosswalk to eliminate manual updates that VA employees often fail to complete. Aligning VA’s facility codes with the ED’s OPEID numbers is essential for accurate data tracking.

C. Educate veterans about student loans

Many veterans tell us they have loans they did not authorize or even know about at the time the loans were taken out.[59] As we note in our report, many veterans are “signed up for loans they did not want or know about and/or [are] wrongly assured their educational benefits from DOD or VA would cover the entire cost of their education.”[60] Travis Craig, an Army veteran, shed light on this practice, noting, “We signed everything on electrical notepads, so us, as students, we didn’t actually know what we were signing for.”[61]

On all of VA’s GI Bill website pages and in its materials, the Department should educate veterans about student loans – including what a “Master Promissory Note” is – a sorely needed improvement because too few students know what “Master Promissory Note” means. To make the obligations of the Master Promissory Note explicit, we also encourage the Committees to work with members of the Education Committees to rename the Master Promissory Note as “Student Loan Contract.”[62]

Summary of recommendations:

- Prohibit VA from publishing “Yelp”-style ratings, which have historically been abused.

- Direct VA to establish a “Risk Index” to allow students to avoid risky schools, and improve “Caution Flags” and the presentation of student veteran complaints.

- Educate veterans about student loans, especially what a “Master Promissory Note” means.

D. Oppose full housing allowance for online-only students – a costly and dangerous proposal

Given the existing and more compelling unmet needs of veterans, we believe the significant federal costs of increasing the monthly housing allowance (MHA) for online-only students should not be the top spending priority for the Veterans’ Affairs Committees. Based on estimates from VA, an annualized cost for increasing MHA for online-only students is expected to cost more than $15 billion over 10 years.[63] We continue to urge Congress to set aside this idea and instead prioritize issues such as GI Bill Parity for Guard and Reserve service, improvements to Survivors and Dependents Chapter 35, and restoration of the GI Bill for defrauded student veterans.

There are strong policy reasons not to pursue full housing allowance for online students:

- Incentivizing Students to Leave Flagship Public Universities. Due to the higher housing allowance, such a policy change would incentivize veterans to leave high-quality, flagship public universities in low-housing cost states – such as Kansas, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Texas – to enroll in national online college chains. Current housing allowance rates for in-person and hybrid learners are based on DOD housing allowance rates (BAH) for an “E-5 with dependents.”[64] Over 60% of DOD’s 339 BAH zones have housing costs less than the national average,[65] in some cases half of the national average. If Congress enacted full housing for online students, veterans at high-quality public colleges would receive less housing money than veterans at low-quality online colleges.

- Marketing Tool for Bad Actors. Predatory schools would use the availability of an increased housing allowance as a selling point to target veterans to attend predatory and exploitative programs. In the aftermath of having finally closed the 90/10 loophole, a shift to a full housing allowance for solely online colleges would re-establish veterans as a target for unscrupulous schools; many of these schools have been sued by law enforcement and fined by federal agencies for defrauding students, and can reasonably be expected to abuse this change.[66], [67]

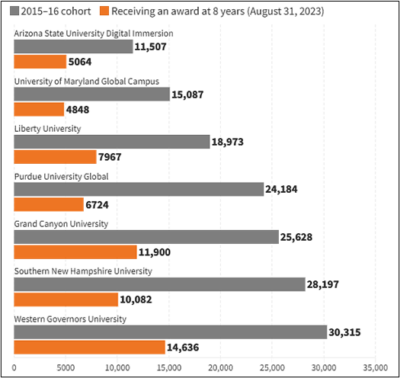

- Fueling Poor Performing Schools. The Committees, student veterans, and taxpayers alike should heavily weigh the demonstrated outcomes of online programs, and consider whether or not these programs are worthy of valuable GI Bill resources. Last month, Inside Higher Ed looked at the 8-year completion rate of the 2015-2016 cohort at large online institutions.[68] The results of that analysis paint a stark picture, as evident in the chart below. Even more specific to this population of students, a 2023 study published by the Annenberg Institute at Brown University found, “Exclusively online students with military service were 11.4 percentage points less likely to earn their bachelor’s degree compared to peers with military service not enrolled in exclusively online programs.”[69]

We urge the Committees not to move forward with any proposals increasing the MHA rate for online-only students. Instead, a near-term solution would be for Congress to direct an unbiased study of online learning outcomes regarding Title 38 veterans’ education benefits.

Summary of recommendations:

● Oppose full housing allowance for online-only students.

7. Change VA’s debt collection practices against student veterans

VA’s debt collection for “retroactive readjustments” of GI Bill benefits awarded to a veteran is of special concern, and we urge the Committees to halt this practice. A “retroactive readjustment” means that VA adjusts a veteran’s GI Bill eligibility after the veteran has already used his GI Bill. If the problem was a VA error and a veteran honorably relied on VA’s procedures, subjecting the veteran to debt collection is unfair.

One problem for veterans is that VA’s letters alerting veterans of a debt are often confusing and sent to outdated addresses. While Section 1019 of the Isakson-Roe Act has addressed some of the underlying factors associated with GI Bill overpayments, the issue of VA debt collection practices has not been comprehensively addressed.

We support the prohibition of VA from executing clawbacks based “solely on administrative error” or “error in judgment,” consistent with 38 U.S.C. § 5112(b)(10). However, it is our firm belief that VA defines administrative error quite narrowly based on the number of clawbacks that still occur.[70] For instance, VA takes the position that if the beneficiary “should have known” they were not entitled to the benefit, then the overpayment was not due solely to administrative error.[71] VA’s assessment of whether a beneficiary should have known they were not entitled to the benefit may disregard the realistic and practical limits of a student veteran’s understanding at the time of payment. It is also possible the student’s misunderstanding stems from information originally provided by VA.

We urge Congress to ban VA’s authority to claw back overpayments when the overpayment is VA’s error and establish a limitation period after which clawbacks are prohibited, except for fraud or malfeasance.

Summary of recommendations:

- Halt the practice of VA “retroactive readjustments.”

- Improve debt notification processes to prevent veterans from being surprised by unclear or outdated notices.

- Establish a limitations period after which GI Bill clawbacks are prohibited, except for fraud or malfeasance.

8. Forbid transcript withholding

Student veterans lack the same protections against transcript withholding that are available to other students in higher education. Colleges frequently withhold their students’ academic transcripts for balances due, even when the debt is disputed, and can withhold transcripts even for minor charges like parking fees. It is one of the most common debt-collection tactics colleges use across all sectors.

Hundreds of student veterans, service members, and their families have brought complaints to us about unfair transcript withholding and its negative impact on their lives. In March 2022, we published a report analyzing how transcript withholding affects the veteran and military communities.[72] Of these student veteran complaints we received:

- 35% are related to disputed debts, often having to do with inaccurate billing or students’ believing their GI Bill or other educational benefits from VA or DOD covered the cost of attendance.

- 34% are general complaints about transcript withholding.

- 20% are related to debt arising from deceptive or predatory institutional practices.

- 7% are related to closed school issues.

- 4% are related to complaints over loans the veterans did not authorize.

Transcript withholding has particularly severe consequences for student veterans. It can prevent them from transferring schools, re-enrolling, or pursuing an advanced degree if they have already graduated. It can also undermine a student’s eligibility for a job interview and even some military promotions.

We urge the Committees to prohibit transcript withholding to collect outstanding debt from former students, irrespective of the periods covered by VA benefits.

Summary of recommendations:

- Establish, as a condition of GI Bill eligibility, that education programs prohibit transcript withholding for students receiving Title 38 education benefits.

9. Ensure orderly processes and restoration of benefits in cases of school closures

Sudden school closures leave students in the lurch, with no end in sight to this alarming trend. Committee members recall the closures of ITT Tech, Corinthian Colleges, Argosy University, and, more recently, three brands owned by the Center for Excellence in Higher Education (CollegeAmerica, Stevens-Henager, and Independence University), plus many others.

Congress could save money by avoiding school closures, by requiring VA to ensure the financial stability of schools eligible for GI Bill (see proposal number 1 on page 2 above).

When a school suddenly closes, student veterans are left in the lurch. We recommend that the Committees require VA to protect student veterans by allowing only financially sound colleges to participate in VA education programs.

In addition, VA should require colleges to put in place safeguards against sudden shut-downs, ensuring orderly closure processes in which students receive adequate advanced notice, viable transfer options, and guaranteed permanent access to their transcripts and records.[73] We believe a 2020 Maryland law provides a valuable model of this approach.[74]

Additionally, the Senator Elizabeth Dole 21st Century Veterans Healthcare and Benefits Improvement Act established the most recent authority for VA to restore GI Bill benefits to students who were pushed out of their programs due to a closure or disapproval before September 30, 2025.[75], [76] However, VA needs to be able to continue to restore benefits when a school closes, or a program is disapproved beyond this date, and we call on Congress to increase the period of coverage to a minimum of five additional years to reflect a date of September 30, 2030, or later.

Finally, a minor technical adjustment related to school closure issues would have a highly consequential impact on student veterans. At present, 38 U.S.C. § 3699 affords veterans to have their benefits restored under limited circumstances, such as a change to “a provision of law enacted after the date on which the individual enrolls at such institution affecting the approval or disapproval of courses under this chapter” or “the Secretary prescribing or modifying regulations or policies of the Department affecting such approval or disapproval.” In consultation with committee staff, we urge the addition of a section iii that states “or for any other reason” because school closure due to a provision of law is a very narrow circumstance, and does not help the tens of thousands of veterans who are affected every year by school closures.

These substantive and technical improvements would significantly enhance the ability of GI Bill students to continue on their educational journey. This is the least they deserve after experiencing the devastating events of a precipitous school closure scenario.

Summary of recommendations:

- Require VA to protect student veterans by allowing only financially sound schools to participate in VA education programs.

- Mandate that all VA-approved schools put in place safeguards against sudden shutdowns, such as adequate advance notice for students, viable transfer options, and guaranteed permanent access to their transcripts and records.

- Extend VA’s expiring authority to restore GI Bill entitlement in school closure or disapproval cases for a minimum of five years.

- Amend 38 U.S.C. § 3699(b)(1)(B) by adding a new section (iii) that states “or for any other reason” because the statute is too narrow at present.

10. Strengthen Veteran Readiness & Employment

As outlined in our previous statements to Congress in 2019, 2022, and 2024, we have continued to receive complaints from veterans about VR&E.[77], [78], [79] Recent complaints continue to tell the story that the process for VR&E benefits is often too complicated and stressful. Veterans get tired of fighting for what they deserve. All too often, some counselors prove to be unresponsive or even antagonistic to a veteran’s interests.

Highlighted below are specific areas of concern raised by veterans who have contacted us recently, followed by recommendations for potential solutions to the challenges veterans face.

A. Veterans feel counselors and the program steer them away from high-quality programs or push them to enroll in low-quality programs.

Many veterans have told us that VR&E counselors steer them away from top colleges and towards low-quality online programs. One recent veteran, a 100% disabled 12-year service member, was denied approval for an Ivy League business school. The counselor dismissed it as too expensive despite its clear career advantages and the likelihood of higher earnings. Veterans find the approval process arbitrary, as the same schools are approved for others.

B. Veterans complain that applying for and using VR&E benefits is too difficult; counselors have denied their admission to the VR&E program, denied their education program, or refused to cover certain programmatic costs without a reasonable explanation, causing tremendous stress.

One veteran was denied funding for essential coursework materials, including a laptop, with no apparent reason beyond a vague claim of insufficient funds. Others report difficulty using VR&E for graduate or professional degrees, with counselors blocking doctoral programs and instead approving degrees that do not align with their disabilities or vocational goals. Some counselors improperly decide that advanced degrees are unnecessary, even after veterans have already started their programs. Many veterans believe counselors lack training to assess how disabilities impact career options.

C. VR&E counselors are often challenging to reach and do not provide timely information and responses to veterans.

Veterans frequently report unresponsive, incompetent, or even antagonistic counselors who seem more focused on disqualifying them than helping. Some are repeatedly reassigned counselors, receiving conflicting guidance and decisions. Many worry about retaliation.

One veteran considered withdrawing from VR&E entirely after a year without a response from his counselor. A medically retired Army veteran struggled for over six months to even start the program.

Based on the issues addressed above, we make the following recommendations for the Committees’ consideration:

- Staff Ratio. Decrease the maximum client-to-counselor ratio from 125 to 85 to ensure veterans receive timely and individualized support. While VA has worked to reduce this number, 125 remains too high for counselors to address veterans’ needs adequately, and veterans continue to report unresponsive counselors.

- Counseling Consistency. Require increased training for VR&E counselors to ensure consistent, high-quality guidance. Too many veterans are steered into low-quality schools while others are approved for top-tier institutions. Counselors should be trained to avoid recommending schools with federal caution flags or law enforcement actions. They should be empowered to approve graduate degrees when needed for veterans to achieve their vocational goals. Additional training and explicit guidance would improve program delivery and the veteran experience.

- System Modernization. Continue improving and modernizing the VR&E case management system to prevent payment delays and reduce administrative burdens. Given the financial hardships many veterans face, timely payments are critical. We commend the e-VA Document Repository and Automation Initiative, which significantly reduces the burden on both veterans and counselors by streamlining required documentation.

- Housing Allowance Parity. Establish a Monthly Housing Allowance (MHA) for VR&E students at rates comparable to the Post-9/11 GI Bill to keep pace with rising living costs.[80]

We thank the Committees for your attention to this critical issue and consideration of these recommendations. We will continue to provide feedback we hear from the veterans with whom we work on an ongoing basis.

Summary of recommendations:

- Decrease the maximum client-to-counselor ratio from 125 to 85 to ensure veterans receive timely, individualized support.

- Mandate standardized, comprehensive training for VR&E counselors to ensure consistent, high-quality guidance, prevent arbitrary school denials, and adequately evaluate graduate and professional degree programs.

- Prohibit VR&E counselors from requiring veterans to attend low-quality online programs instead of high-quality, reputable colleges and from imposing sudden enrollment deadlines that force veterans into suboptimal education choices, and require reasonable accommodations for transcript access and administrative delays.

- Direct VA to modernize the case management system to prevent payment delays and reduce administrative burdens on veterans.

- Establish Monthly Housing Allowance parity between VR&E and Post-9/11 GI Bill students to reflect real cost-of-living needs.

11. Pass the Guard and Reserve GI Bill Parity Act so every day of service counts

We call on Congress to address a long overdue issue affecting the eligibility of reserve component members for the Post-9/11 GI Bill® by passing the Guard and Reserve GI Bill Parity Act. The current law mandates that Guard and Reserve Members must have served at least 90 cumulative or 30 continuous days on active duty to accrue “qualifying days,” creating a disadvantage in accessing their deserved GI Bill educational benefits. Despite the obligation for reserve component members to “serve in uniform” and fulfill duty responsibilities for a minimum of 39 non-consecutive days each fiscal year, these periods of service do not contribute toward Post-9/11 GI Bill eligibility.

This discrepancy disadvantages reserve component members compared to their active component counterparts. While active duty members can receive Post-9/11 GI Bill credit for a training day, reservists currently cannot receive credit for the same service. The increased reliance on reserve capabilities has underscored the necessity for component interoperability. Unfortunately, the strides made in achieving interoperability have not been complemented by fair recognition and rewards for the skills and efforts required.

An Operational Assessment of Reserve Component Forces in Afghanistan, conducted by the Institute for Defense Analyses, revealed no discernible difference in performance between components in Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. The study emphasizes that reserve forces were fulfilling their assigned tasks without significant variations from their active-duty counterparts. The shared burden and risk between both components highlight the importance of acknowledging the contributions of Guard and Reserve members.

To address this disparity, we strongly urge Congress to count all paid points days of Reserve and National Guard service members towards receiving the Post-9/11 GI Bill.[81] This encompasses days for training, active military service, inactive training, and general duty. This adjustment aims to ensure equitable treatment, recognizing the crucial contributions of reserve component members to military readiness. It is essential to promote fairness and acknowledge their vital role without compromising the integrity of the GI Bill system.

Summary of recommendations:

- Pass the Guard and Reserve GI Bill Parity Act so that a day in uniform truly counts as such.

Conclusion

Veterans Education Success sincerely appreciates the opportunity to express our legislative priorities before the Committees. The higher education industry continues to evolve in these dynamic times, and we emphasize the importance of maintaining high standards. Student veterans, taxpayers, and Congress must expect the best outcomes from using hard-earned GI Bill benefits.

We look forward to enacting these priorities and are grateful for the continued collaboration opportunities on these initiatives.

Information Required by Rule XI2(g)(4) of the House of Representatives

Pursuant to Rule XI2(g)(4) of the House of Representatives, Veterans Education Success has not received any federal grants in Fiscal Year 2025, nor has it received any federal grants in the two previous Fiscal Years.

[1] Veterans Education Success. Schools Receiving the Most Post-9/11 GI Bill Tuition and Fee Payments Since 2009 (Mar. 2018). https://vetsedsuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/gi-bill-cumulative-revenue-brief-2.pdf.

[2] Id.

[3] Veterans Education Success. Should Colleges Spend the GI Bill on Veterans’ Education or Late Night TV Ads? And Which Colleges Offer the Best Instructional Bang for the GI Bill Buck? (2019), https://vetsedsuccess.org/should-colleges-spend-the-gi-bill-on-veterans-education-or-late-night-tv-ads-and-which-colleges-offer-the-best-instructional-bang-for-the-gi-bill-buck/.

[4] See also U.S. Dept. of Education, Federal Student Aid Fiscal Year 2024 Annual Report (2024), https://studentaid.gov/sites/default/files/fy2024-fsa-annual-report.pdf, (p. 140-143) (“FSA also received a disproportionate number of complaints from predominantly online schools. FSA received 2,764 complaints (23%) about schools where more than 80% enrolled exclusively online. In contrast, these schools accounted for only 9% of enrollment in Title IV-eligible schools during the 2023-24 school year…”).

[5] Carli Teproff, Now defunct for-profit college must pay the government $20 million, a court rules, Miami Herald (Feb. 21, 2017), https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/education/article134161714.html.

[6] U.S. Department of Justice Press Release, For-Profit Trade School Owner Charged with Defrauding VA, Student Veterans (Nov. 23, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndtx/pr/profit-trade-school-owner-charged-defrauding-va-student-veterans.

[7] Dana Treen, FBI raids Jacksonville offices of business college, The Florida Times-Union (May 16, 2012),

[8] U.S. Department of Justice Press Release, United States Prevails in Civil Suit Against For-Profit College Chain and its President for False Claims Act Violations (Feb. 21, 2017),

[9] Eva-Marie Ayala, Hundreds of veterans scramble after Garland for-profit college closes, The Dallas Morning News (Sept. 28, 2017), https://www.dallasnews.com/news/education/2017/09/28/hundreds-of-veterans-scramble-after-garland-for-profit-college-closes/.

[10] Id.

[11] U.S. Department of Justice Press Release, For-Profit Trade School Owner Charged with Defrauding VA, Student Veterans (Nov. 23, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndtx/pr/retail-ready-owner-forfeit-72m-va-tuition-fraud.

[12] Id.

[13] U.S. Department of Justice Press Release, Owner of Local Technical Training School Sentenced for Defrauding the VA out of almost $30 Million in G.I. Bill Education Benefits (Oct. 27, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdca/pr/owner-local-technical-training-school-sentenced-defrauding-va-out-almost-30-million-gi.

[14] Veterans Education Success, Our Press Release: Largest Post 9/11 GI Bill Fraud Case Yields Guilty Pleas (Jun. 28, 2023),

[15] U.S. Department of Justice, Justice Department Announces Enforcement Action Involving Over $100 Million in Losses to Department of Veterans Affairs (Sept. 16, 2022),

[16] 38 U.S.C. § 3672 has almost no requirements. It also incorporates, by reference, the program approval requirements of Chapters 34 and 35, but those are also minimally effectual; they only forbid, for example, bartending and personality development courses, and they restrict “radio” courses, which indicates an out-of-date statutory framework. 38 U.S.C. § 3675 (approval of accredited courses) relies heavily on the school’s accreditation, but some accreditors offer no meaningful quality control, such as ACICS, which accredited ITT Tech and Corinthian Colleges. § 3675(b) also requires that the school meet the criteria in paragraphs (1), (2), (3), (14), and (15) of 38 U.S.C. § 3676(c). While 38 U.S.C. § 3676 (approval of nonaccredited courses) has more restrictions, many are undefined, including no definition of “quality” in (c)(1); no definition of teacher “qualifications” in (c)(4); no definition of “financially sound” in (c)(9) (which could easily be defined by reference to U.S. Department of Education standards); an inadequate ban on deceptive advertising in (c)(10) (which should be clarified to ban any school that has faced legal or regulatory concerns over its advertising in the prior 5 years); and no definition of “good character” in (c)(12) (which should be clarified to ban administrators and teachers who have faced legal or regulatory action or any action by a licensing board).

[17] U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General, “Monthly highlights: January 2025” (Feb. 2025), https://www.vaoig.gov/sites/default/files/document/2025-02/monthly_highlights_january_2025_1.pdf.

[18] 38 U.S.C. § 3523(c).

[19] Quotes come from the more than 4,000 student veterans who have brought complaints to Veterans Education Success. For privacy protection, the students’ names are withheld.

[20] Currently, there is no requirement in Title 38 that schools devote the necessary resources to competent administration of VA programs. Congress should mandate that institutions demonstrate to the Secretary that they are capable of adequately administering the programs and that they have committed adequate administrative resources. It should also require that schools pledge to fully cover the tuition and housing costs of VA-supported students if the school suddenly loses eligibility due to institutional error, including paperwork non-compliance. Committee members may recall the problems at Howard University, when 52 VA-supported students enrolled in 14 programs at Howard suddenly discovered their programs were not properly approved for GI Bill and VR&E. The DC State Approving Agency (SAA) said the issue boiled down to failure by Howard to submit the proper paperwork. The programs affected included Howard’s medical school, law school, and Master in Social Work program. It took eight months to get the approvals cleared up. During this time, students experienced immense uncertainty and undue anxiety. They faced the possibility of having to withdraw from school, pay out-of-pocket to cover housing and living costs, or seek loans from the school and external sources, and they experienced significant stress due to the uncertainty of the situation. This scenario highlighted the challenge associated with Title 38 benefits and the relationship between VA, the SAA, the institution, and the student. Unfortunately, we do not believe this to be an issue isolated to one school. In some cases, school certifying officials (SCOs) are expected to administer benefits for well over VA’s recommended ratio of support staff to students, 1 to 200. Even with this ratio, the duties of SCOs often go well beyond the responsibilities of certifying benefits, making their responsibilities increasingly difficult to handle.

[21] Veterans Benefits Administration, Office of Education Service – Oversight and Accountability Division, Standard Operating Procedure, Risk Based Surveys (Jan. 2, 2024). In the Standard Operating Procedure, VBA includes material regarding the process for requesting more documentation from unaccredited schools in program approval.

[22] Veterans Education Success, Should Colleges Spend the GI Bill on Veterans’ Education or Late Night TV Ads? (Apr. 2019), https://vetsedsuccess.org/should-colleges-spend-the-gi-bill-on-veterans-education-or-late-night-tv-ads-and-which-colleges-offer-the-best-instructional-bang-for-the-gi-bill-buck/.

[23] For an historical explanation of the dangers of education programs that lack teaching, see David Whitman, The Cautionary Tale of Correspondence Schools, New America (Dec. 11, 2018), https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/cautionary-tale-correspondence-schools/.

[24] Veterans Education Success, Congressional and Administration Priorities for the Next Congress, Submitted to the Subcommittee on Economic Opportunity, Committee on Veterans Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives (Dec. 8, 2020), https://vetsedsuccess.org/our-written-testimony-for-the-house-veterans-affairs-economic-opportunity-subcommittee-hearing-on-2021-legislative-priorities/#_ftn1.

[25] Denis, Doug, “Interview with Student Veteran: Doug Denis” (Jun. 28, 2024), https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ODE10wEG99-0bKv9Khr8jbGYnPUFiEWN/view?usp=sharing.

[26] United States of America v. $115,800.00 in U.S. Currency Funds, (Jan. 6, 2023), https://vetsedsuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/House-of-Prayer-Bible-Seminary.pdf.

[27] Veterans Education Success, Our Letter to VA and Georgia SAA Regarding House of Prayer Christian Church (Aug. 2020), https://vetsedsuccess.org/letter-to-va-and-georgia-saa-regarding-house-of-prayer-christian-church/.

[28] United States Attorney’s Office, Northern District of Texas Press Release, For-Profit Trade School Sentenced to Nearly 20 Years for Defrauding VA, Student Veterans (Sept. 22, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndtx/pr/profit-trade-school-sentenced-nearly-20-years-defrauding-va-student-veterans.

[29] Public Law 118-210, Senator Elizabeth Dole 21st Century Veterans Healthcare and Benefits Improvement Act, 118th Congress, 2nd Session (2024), https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/8371.

[30] Section 212(c)(2)(C)(iii) states, “the enrollment of the individual in a program of education to continue education in such field of study.”

[31] VA records received in response to a FOIA request. On file at Veterans Education Success.

[32] VRRAP had milestone payments similar to VET TEC.

[33] Public Law 117-2, American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Sec. 8006(d), 117th Congress, 1st Session (2021), https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ2/PLAW-117publ2.pdf.

[34] The Improving Transparency of Education Opportunities for Veterans Act, P.L. 112-249 (2012), codified at 36 U.S.C. § 3698(c)(3)(A) and (B).

[35] The interagency research team consisted of staff from VA’s National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics (NCVAS), the U.S. Census Bureau, and the American Institutes for Research (operating as special-sworn-status employees under the control of the Census Bureau and abiding by the laws governing the handling of sensitive federal data) and they were able to combine data from VA, the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), the Department of Defense (DOD), Internal Revenue Service (IRS), U.S. Census Bureau, and National Student Clearinghouse (NSC).

[36] Radford, A., Bloomfield, A., Bailey, P., Webster, B. H. Jr., & Park, H. C., “A First Look at Post-9/11 GI Bill-Enlisted Veterans’ Outcomes” (2024), American Institutes for Research; U.S. Census Bureau; and National Center for Veterans Analysis & Statistics, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, https://vetsedsuccess.org/a-first-look-at-post-9-11-gi-bill-eligible-enlisted-veterans-outcomes/.

[37] Radford, A. W., Mayer, K. M., Bloomfield, A., Bailey, P., Webster, B. H. Jr., & Park,

- C., “Which Veterans are Forgoing Their Post-9/11 GI Bill Benefits?” (2025), American Institutes for Research; U.S. Census Bureau; and National Center for Veterans Analysis & Statistics, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, https://vetsedsuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/REPORT_Which-Veterans-Are-Forgoing-Their-Post-9-11-GI-Bill-Benefits.pdf.

[38] Jiang, J. Y., Mayer, K. M., Le, V., & Radford, A. W., “Post-9/11 GI Bill

Access and Uptake: Insights and Recommendations from Veterans” (2025), American

Institutes for Research, https://vetsedsuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/REPORT_Post-9-11-GI-Bill-Access-and-Uptake.pdf.

[39] Radford, A. W., Bloomfield, A., Bailey, P., Mayer, K. M., Webster, B. H. Jr., & Park, H. C., “A Deeper Look at Post-9/11 GI Bill Outcomes for American Indian/Alaska Native, Black, and Hispanic Veterans” (2025), American Institutes for Research; U.S. Census Bureau; and National Center for Veterans Analysis & Statistics, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, https://vetsedsuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/REPORT_A-Deeper-Look-at-Post-9-11-GI-Bill.pdf.

[40] Id.

[41] Radford, A. W., Bailey, P., Bloomfield, A., Webster, B. H. Jr., & Park, H. C., “Post 9/11 GI Bill Eligible Enlisted Veterans’ Enrollment and Outcomes at Public Flagship Institutions” (2024), American Institutes for Research, U.S. Census Bureau, and National Center for Veterans Analysis & Statistics, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, https://vetsedsuccess.org/post-9-11-gi-bill-eligible-enlisted-veterans-enrollment-and-outcomes-at-public-flagship-institutions-with-a-focus-on-the-great-lakes-region/.

[42] Radford, A. W., Bailey, P., Bloomfield, A., Rockefeller, N., Webster, B. H. Jr., & Park, H. C., “How Do Veterans’ Outcomes Differ Based on the Type of Education They Received? And How are Veterans Who Have Not Used Their Education Benefits Faring?” (2024), American Institutes for Research, U.S. Census Bureau, and National Center for Veterans Analysis & Statistics, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, https://vetsedsuccess.org/post-9-11-gi-bill-benefits-how-do-veterans-outcomes-differ-based-on-the-type-of-education-they-received-and-how-are-veterans-who-have-not-used-their-education-benefits-faring/.

[43] Id.

[44] Id.

[45] Id.

[46] Id.

[47] Id.

[48] Id.

[49] Bloomfield, A., Radford, A. W., Bailey, P., Webster, B. H. Jr., & Park, H. C, “Post-9/11 GI Bill eligible enlisted veterans’ enrollment outcomes at public flagship institutions, with a focus on the Great Lakes region” (2024), American Institutes for Research; U.S. Census Bureau; and National Center for Veterans Analysis & Statistics, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, https://vetsedsuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/pgib-outcomes-public-flagship-great-lakes.pdf.

[50] Kacie Kelly and Dr. Caroline Angel, George W. Bush Presidential Center, Common Questions to Better Serve Our Vets (Apr. 2020), https://www.bushcenter.org/publications/common-questions-to-better-serve-our-vets.

[51] The U.S. Department of Education is broadly prohibited by law from sending data out; however, they would be able to accept data and run analyses to produce findings for publication.