I. Executive Summary

The Post-9/11 GI Bill represents an idealized college financing plan, covering full tuition and fees at public colleges (or up to $29,000 at private institutions), plus housing and book allowances. This comprehensive support makes it an important model and cautionary tale for Title IV federal student aid programs. At a time when Congress is reimagining the Higher Education Act, the GI Bill’s outcomes offer critical insights for broader student aid reform.

An unprecedented interagency data-sharing project analyzed the student records and IRS earnings of the entire universe of Post-9/11 GI Bill enlisted veterans and their use of the Post-9/11 GI Bill, utilizing hitherto unavailable federal data about their military service, academic aptitude and preparation, their journey through the postsecondary system, and their IRS earnings after education. This analysis explores the interagency study’s findings and concludes that the interagency study is important not only for its findings on the GI Bill student outcomes for 2.7 million American enlisted veterans, but also for its implications for the much larger amounts of federal funding for federal student aid, which has never generated similar data.

The interagency study published six reports (available here) from a team of researchers from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, U.S. Census Bureau, and American Institutes for Research (who were embedded as Special Sworn Status employees of the Census Bureau and followed all Census Bureau and IRS laws regarding proper handling of confidential information). The report drew on IRS earnings data, student records from the National Student Clearinghouse, and information from the U.S. Department of Defense (providing servicemembers’ records of military occupation and service as well as their academic aptitude and preparation test results upon their entry into military service), U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (multiple sources of records) and the U.S. Census Bureau (providing a plethora of data),

This comprehensive study – utilizing the incredibly large dataset of 2.7 million Americans and their GI Bill outcomes – revealed three crucial lessons:

A. Quality Matters

Institution quality significantly impacts outcomes, and VA’s current quality controls remain inadequate. The interagency team found:

- Veterans who attended for-profit institutions consistently earned less than those at public institutions, despite for-profit institutions’ charging VA higher tuition (nearly double for Associate degrees).

- Veterans’ completion rates at for-profit colleges were 15% lower than at public colleges, even after controlling for veteran characteristics.

- In one of the strongest correlations found by the interagency team, college completion and earnings rose with each quintile increase in a college’s instructional spending, yet only 1% of veterans attended colleges with the highest instructional spending. (Similarly, in an earlier, separate study conducted by Veterans Education Success, seven of the ten schools receiving the most GI Bill funding spent less than one-third of tuition on actual education, with poor completion rates (under 28%) and earnings outcomes; they also faced state and federal law enforcement actions for deceptive practices).

B. Individual Preparation Matters

Veterans’ academic preparation before military service strongly predicted GI Bill usage and outcomes:

- Higher AFQT scores (measuring academic preparation or aptitude at the time of military enlistment) consistently and strongly correlated with higher GI Bill usage, graduation rates, and earnings.

- A 10-point gap in GI Bill usage remained between the lowest and highest AFQT score quintiles even after controlling for other factors.

- The gap in college completion rates between the lowest and highest AFQT quintiles was 19 percentage points, with higher scores strongly associated with higher completion rates.

- Earnings also correlated with AFQT scores, although demographic differences and military factors explained some of the earnings gap.

C. Guidance and Pathways Matter

Many veterans do not use their GI Bill benefits, and usage varies significantly based on information access and guidance:

- Nearly 2 in 5 veterans did not use their GI Bill benefits.

- Usage rates varied by military branch. (Air Force veterans were the least likely to use benefits, at 45% non-use; Marines were the most likely, at only 30% non-use.)

- Rural and micropolitan area veterans were less likely to use their benefits.

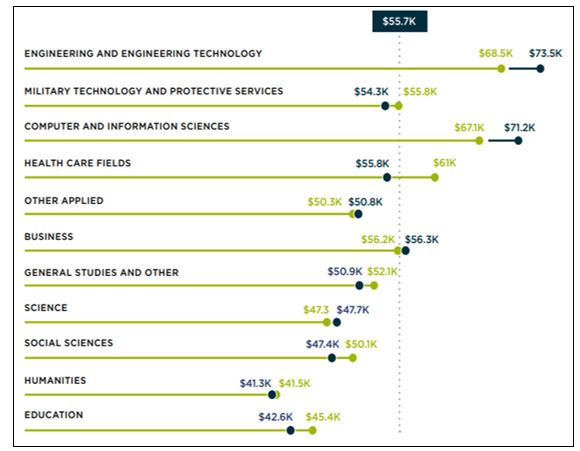

- Field of study significantly impacted earnings, with engineering and computer science graduates earning substantially more than those in education, humanities, or social sciences.

- In qualitative interviews, the top reasons veterans gave for their non-use of GI Bill benefits included lack of information about expiration dates and transfer requirements.

- Veterans also report being targeted by aggressive and deceptive recruiting practices that channel them into low-quality programs

Implications for Title IV Reform

The groundbreaking interagency study of 2.7 million veterans and their GI Bill outcomes demonstrates that removing financial barriers, alone, is not sufficient to ensure student success. Quality institutions, adequate student preparation, and proper guidance are essential components of effective higher education policy.

Especially at a time when resources are under the greatest stress due to efforts to cut costs, it is critical that policymakers redirect federal policy in the direction of extracting the best outcomes from every aid dollar through insistence on quality. Data from the interagency research team at the Census Bureau found that instructional spending is strongly correlated with higher completion rates and higher post-enrollment earnings, and this held true across sex, race, rurality, and military rank, as well as overall among all veterans. Federal policymakers should consider imposing a floor on the portion of a college’s tuition and fees that must be spent on the substance of students’ education to ensure that at least some portion of tuition dollars financed with federal aid is used to actually teach students.

Institutional risk-sharing in student loan losses could also promote acceptable repayment outcomes. Financing known low-wage academic fields with student loans may make sense to a young person hoping that he or she will be the exception to the abysmal future earnings data for that field of study, but institutions that knowingly recruit students into such programs should be required to share in the repayment pain that solely falls on their former students. Differences in outcomes by field of study may require consideration of new policy refinements, such as differential pricing and/or differential subsidies, perhaps along with enrollments caps.

The GI Bill also teaches us that an individual student’s preparation and guidance are critical to his or her academic success. The interagency research team at the Census Bureau found one of the strongest correlations between a veteran’s AFQT score (representing his or her academic preparation and skills at the time of enlistment into the military) and his or her later usage of the GI Bill, college completion, and earnings. Sadly, the federal government has had an uneven record on both preparing students for higher education and guiding them in their college pathway, primarily because of the federal government’s limited jurisdiction and authority in K-12 education. Credible higher education policy cannot, however, merely bemoan the reality that too many aided students enroll in postsecondary programs unprepared: it should devise a policy response. That policy response has historically taken the form of the TRIO programs and the GEAR-UP program, and those should be expanded. Additional policy thought should also be given to the creation of pre-collegiate remedial high school programs for eligible students.

The interagency research team’s findings clearly demonstrate that quality matters — in institutions, in preparation, and in guidance.

II. Introduction

On its face, the GI Bill represents an idealized college financing plan. As such, it could be an important model – as well as, as this paper will set forth, a cautionary tale – for Title IV financing and structure.

For decades, a central tenet of advocacy for broad college access has been the elimination of financial barriers. Different policy camps may take markedly divergent paths to that goal, but the notion that costs constitute the primary obstacle is the premise on which advocates of free college and those who argue for targeted means-tested vouchers seem to agree.

The GI Bill is idealized in the sense that it covers up to four academic years of full tuition and fees at any public college in America – or an amount capped at just under $29,000 at private institutions – as well as a housing stipend (tied to the local costs) and an allowance for books and supplies. Lessons learned from robust analysis of GI Bill outcomes, therefore, can shed important light on non-financial policy levers that may apply across the board to all aided students. How do students perform when financial stress is removed? What are the remaining obstacles, if any, to their success as students and, later, as members of the civilian workforce?

III. Public Support for College Access

The notion of governmental action to remove financial barriers to college, at least for some prospective students, in the U.S. has a rich history dating back to the 19th century. While the states were the primary sponsors of affordability by developing low- or no-tuition public institutions, the Land-Grant College Act (1862) was the first significant federal intervention for broader access. This federal statute, also known as the Morrill Act, granted federal land to states to establish public universities focused on agriculture and mechanical arts. Interestingly, the generous federal grants carried no pricing mandates and did not require colleges supported by them to be free. This was mainly because a pricing mandate was thought unnecessary, as public colleges were either free or extremely low-cost at that time. These state institutions were meant to expand access to higher education beyond the small population of wealthy elites who attended Eastern colonial-era colleges, with seemingly hereditary access.

The unspoken and unmandated assumption of price affordability (i.e., free or low-tuition) held from the late 19th-century establishment of numerous normal schools and regional state universities through the mid-20th century. The City University of New York, initially named the Free Academy and founded as the first free public institution of higher education in the U.S. in 1847, remained tuition-free until 1976, when the city’s financial crisis led to the introduction of tuition.[1] It remains one of the most affordable public institutions, with a $6,930 tuition for in-state residents.

Similarly, the crown jewel of American public higher education, the University of California System, was tuition-free for state residents until 1968.[2] Today, undergraduate in-state tuition and fees run at $21,101 for the 11 percent of applicants admitted to UC Berkeley who are “in-state.” Free or low tuition was even incorporated into Article XI, Section 6 of the Arizona Constitution, which states: “The university and all other state educational institutions shall be open to students of both sexes, and the instruction furnished shall be as nearly free as possible.” Today, in-state undergraduate tuition at the University of Arizona is $13,900. These figures do not include mandatory fees for labs or books and supplies.

Two post-War developments further enshrined access and affordability as appropriate public policy goals for the nation. First, the post-World War II GI Bill (1944) provided higher education benefits to millions of veterans, effectively rendering all public institutions free to them. The program’s incredible success was a significant factor in the adoption of vouchers, as opposed to direct aid to institutions, in the 1972 amendments that essentially created the basic framework of today’s federal aid system.[3] In adopting that model, however, Congress also inadvertently adopted its lack of robust price discipline mechanisms, a fateful decision that paved the way for a voucherized student aid system that has failed to control price inflation. The second decisive national advancement in affordability and access was the emergence of the nationwide community college movement, most grandiosely embodied in the California Master Plan (1960).

America’s Golden Age of Higher Education began to fade as economic pressures and changing political attitudes led to increased tuition in the 1970s and 1980s. The states began reducing funding for public higher education, leading to gradually increasing tuition.[4] Worse yet, tuition costs rose simultaneously as wages began to stagnate[5] in the 1970s, creating a perfect storm for low- and middle-income families. With the states confronting a brewing “taxpayer revolt” after the passage of the extremely popular California Proposition 13 in 1978, which capped property taxes, states began to further cut their investments in their colleges[6] and the federal government stepped in with a series of higher education policy responses, including increased grants and vastly expanded and heavily subsidized student loans through the Middle Income Student Assistance Act. A mere three years later, however, to control the growing federal budget deficit, much of the loan subsidies were stripped out in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981, even as student loans began to play an ever larger role as the dominant mechanism of financing college access (but not affordability). This left colleges with lower investments from both the states and federal government.

The policy pivots away from affordable prices and toward debt-financing of higher education did not take long to generate a massive debt bubble. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York reported total outstanding student loan debt at $1.62 trillion in the last quarter of 2024,[7] making educational debt the third-largest category of consumer debt after mortgages and auto loans, having overtaken credit card balances. More ominously, student debt has followed a steeper path than other consumer credit categories over the past two decades – a trend that shows little sign of easing,[8] mainly due to ever-increasing college costs. The public and policymakers have become increasingly alarmed about whether the existing outstanding federal student loan portfolio can ever be realistically repaid. Data from the Department of Education’s Federal Student Aid Office indicate that 50-60% of loans in repayment status were in negative amortization, e.g., failing to cover even the interest due on the loans,[9] inviting comparisons to the mortgage bubble that triggered the 2008 financial crisis.[10]

Concern about the growing phenomenon of educational debt rekindled interest in various configurations of free college. The Kalamazoo Promise (2005) marked a watershed moment as one of the first large-scale, place-based promise programs. Anonymous donors in Kalamazoo, Michigan, established this program to cover tuition at Michigan public colleges and universities for graduates of Kalamazoo Public Schools. Its success inspired many similar programs across the country. Tennessee Promise launched in 2015, becoming the first statewide program to offer tuition-free community college. Rhode Island Promise (2016) followed Tennessee’s model. Oregon Promise began in 2016, and Nevada Promise Scholarship started in 2017. The concept gained national momentum when President Obama proposed America’s College Promise in 2015, which would have made community college free nationwide. While this proposal did not pass Congress, it accelerated state and local adoption. These programs were designed to piggyback the existing aid system and offered to backfill qualified applicants’ unmet need after federal grant aid through “last dollar” packaging rules. They did, nevertheless, aspire to the recreation of tuition-free access policies as alternatives to debt financing.

Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign brought a more expansive notion of free public college into mainstream discourse and made what was initially a fringe idea into a potent political movement. The Sanders version of free public college was markedly different from neoliberal variants that relied on means-tested vouchers. His version of free college would eliminate tuition at public colleges by providing a two-to-one federal-state matching grant to all public institutions. Sanders specifically cited the earlier history of free public institutions as the end goal of his proposal and argued against much of the conventional wisdom of higher education experts.

In defense of their vision, free public college advocates applied the very arguments that student aid advocates had used for decades but took those to their extreme logical conclusions in the form of tuition-free college for all. Specifically, these arguments focused on equity and democratic access to higher education, economic mobility, higher education as a public good in civic society, and higher education as the modern-day equivalent of a high school diploma in the Information Age. While student aid advocates had used these arguments to push for increased federal and state aid to students to offset the tuition they faced, the free college movement instead took these arguments to make the case that college should be tuition-free for all.

Unnoticed in the free college-versus-student aid debate was the fact that the nation had already launched an extraordinarily generous free college program for its veterans through the Post-9/11 GI Bill (hereinafter “GI Bill”). The bill was enacted on June 30, 2008, as Public Law 110‑252, and went into effect on August 1, 2009. GI Bill‑eligible veterans can receive benefits that fully cover their tuition and fees at any public college or university (or a capped amount that can be spent at a private college through a matching program), a monthly housing allowance based on the local cost of living, and a stipend for books and supplies. GI Bill benefits also may be transferred to a spouse or dependent.

Examining the Post-9/11 GI Bill’s outcomes is therefore instructive for any assessment of free college or more enhanced student aid, as it is for Title IV structuring and finance.

IV. Topline Lessons from the GI Bill

A. Quality Matters

The first lesson for Title IV from the GI Bill is that institutional quality matters because the system is delegating judgment to individuals. Student veterans choose their colleges, but they do so relying on the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)’s “stamp of approval” that a postsecondary program is worth their time, sacrifice, and hard-earned GI Bill. The individual veterans who seek help from us at Veterans Education Success commonly express anger that VA would approve schools already known for producing poor outcomes or that were already under a law enforcement cloud. Regarding obviously subpar quality, one veteran told us:

“There are … issues such as the school replaying free web seminars as their own training and using unqualified people to lead the classes. They literally go to Youtube, find the free course by someone else, then they play that during the ZOOM meeting and call it training. Everything they are doing could have been done by me for free… They have also attempted on two occasions to place me in classes before I ever had the prerequisites to attend, they have me in classes that are not part of the program and do not serve a purpose except to show me in class…”[11]

The rationale behind the modern GI Bill is the same as it was behind the original GI Bill (the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944): To ensure that those who served the country in uniform would receive the support needed to successfully transition back into the civilian economy.[12] The original GI Bill also created programs to help World War II veterans with homeownership and economic support.[13]

The original GI Bill was a roaring success. Indeed, many economists credit the original GI Bill with creating the rapid expansion of America’s middle class in the decades immediately following WWII. Millions of veterans came home and enrolled in college, bought homes, and entered the workforce with new skills. An estimated 8 million World War II veterans used the education benefits, driving the expansion of universities and community colleges.[14] [15]

Predatory Abuses and Poor Outcomes at Some Programs Emerged as Early as WWII

While largely a success, the original GI Bill also led to an explosive growth in the number of for-profit trade schools, many created exclusively to enroll veterans. Many “fly by night” training schools proliferated in the late 1940s and 1950s, offering shoddy training at inflated costs to take advantage of the maximum amount covered by the GI Bill.[16]

Low-quality and predatory programs continued to be a problem in the following decades. In 1950, following a critical assessment by the Veterans Administration finding poor outcomes at for-profit schools and a call to action by President Truman, Congress established the House Select Committee to Investigate Educational Training and Loan Guarantee Programs Under the GI Bill.[17] The so-called Teague Committee, named after its Chairman, Representative Olin Teague, was tasked with examining the abuses that plagued the original GI Bill. The Teague Committee found that “proprietary profit schools below the college level” had falsified cost data and attendance records, overcharged for books and supplies, and billed for students not enrolled.[18] The Select Committee concluded:

“Many schools have offered courses in fields where little or no employment opportunity existed. Certain trades and vocational fields such as tailoring, automobile mechanics, and cabinetmaking have been seriously overcrowded by trade schools. Criminal practices have been widespread among this class of schools. Convictions have been obtained in approximately 50 school cases. Approximately 90 cases are pending and millions of dollars in overpayments have been recovered. Many new cases are developing.”[19]

Quality Concerns Today: Census Bureau Findings

Predictably, low-quality and predatory colleges have abysmal outcomes.

This past year, we wrapped up a ten-year effort to create an interagency data-sharing project to analyze GI Bill student outcomes. The results of that interagency data-sharing are the first-ever comprehensive understanding of the economic outcomes for enlisted veterans who use the Post-9/11 GI Bill. This unprecedented interagency data-sharing drew on data from the VA’s National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics (NCVAS), the U.S. Census Bureau, the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), the Department of Defense (DOD), the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the U.S. Census Bureau, and the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC).[20]

The interagency research team (with representatives from VA and the Census Bureau) was able to draw clear conclusions about veterans’ GI Bill outcomes by accounting for sociodemographic data as well as military rank, military occupation, service in hostile war zones, and academic preparation at the time of enlistment (by linking data from DOD).[21]

Because the dataset included 2.7 million enlisted veterans, the research was able to compare similarly situated veterans (drilling down to such details as comparing all veterans who are Black, female, single parents, living in rural areas, who left the military at the rank of E6, and who had the same military occupation and service).[22] Moreover, by including data from the DOD such as military occupation, rank, and other details of their service, as well as the testing of servicemembers’ academic preparation – through the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) – the research team was able to isolate key factors at play.[23]

The findings highlight consistent quality concerns in some colleges:

- Veterans pursuing nondegree programs (such as certificate programs) and two-year degree programs (i.e., associate degrees) consistently earned less if they attended a for-profit program rather than a public program, even though for-profit programs consistently charged VA a higher tuition than public programs (and almost double the cost for associate degrees).[24]

- For degree programs, about 43% of veterans (or 87% of GI Bill Users) used GI Bill benefits at some point during their GI Bill use at an IPEDS provider, whereas 6% of veterans (or 11% of GI Bill Users) did so at a non-IPEDS provider.[25]

- Veterans who pursued degrees at IPEDS institutions were earning more than those who did so at non-IPEDS providers, for every veteran group examined.[26]

- Across both non-IPEDS and IPEDS providers, earnings at for-profit providers were lower than at public providers.[27] A regression analysis of just IPEDS providers found that this remained true at the two-year level, even after accounting for other veteran characteristics. Two-year for-profit colleges also cost the GI Bill program more than twice as much as two-year public colleges, in terms of average payment per veteran.[28]

- At the four-year level, veterans’ average completion rate was nearly double that of financially independent students, generally,[29] but veterans’ completion rate at for-profit colleges was 15% lower than for veterans at public colleges, even after controlling for veteran and military characteristics in a regression analysis.[30]

- Veterans’ college completions and earnings were higher when their college’s instructional spending was higher – and this was true across sex, race, rurality, and military rank, as well as overall among all veterans – yet only 1% of veterans attended colleges with the highest instructional spending.[31]

- Veterans at public flagship universities were significantly more likely to graduate and were more likely to earn more money than at other four-year institutions in the same states – but veterans were less likely than non-veterans to attend such public flagship universities.[32]

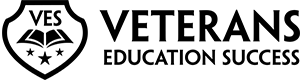

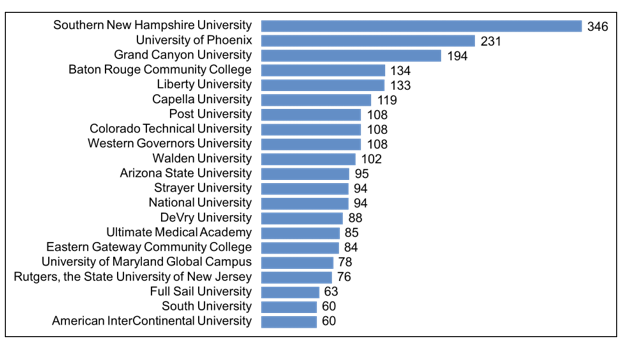

Non-veterans also experience worse outcomes at for-profit and online colleges. In January 2025, Inside Higher Ed looked at the 8-year completion rate of the 2015-2016 cohort at large online institutions.[33] The results of that analysis paint a stark picture, as evident in Figure 1 below.[34]

Figure 1. Institutions with Large Online Enrollments: Eight-Year Completion Figures

Even more specific to the population of student veterans, a 2023 study published by the Annenberg Institute at Brown University found, “Exclusively online students with military service were 11.4 percentage points less likely to earn their bachelor’s degree compared to peers with military service not enrolled in exclusively online programs.”[35]

The Worst Quality Programs Receive the Most GI Bill Funding

Today, veterans count on VA’s program eligibility as a “stamp of approval” that ensures basic quality, but too many approved programs fail to educate veterans, and some cause serious harm. This leaves these students with worthless credits, burdensome debts, and wasted benefits. Yet, despite providing poor results, many of these programs and schools continue to rake in millions of taxpayer dollars through the recruitment and exploitation of veterans and the abuse of their hard-earned GI Bill benefits.

Some of the lowest-quality schools receive the most GI Bill funding. Our research found that, from 2009 to 2017, eight of the 10 schools receiving the most Post-9/11 GI Bill funds accounted for 20% of all GI Bill payments, amounting to $34.7 billion – as shown in Table 1 below.[36] Even more concerning, seven of these 10 schools had high numbers of student complaints and had faced state and federal law enforcement actions regarding allegations of deceptive advertising, predatory recruiting, and fraudulent loan schemes.[37]

Table 1: Top 10 Recipients of Post-9/11 GI Bill Tuition and Fee Payments, FY2009-2017

| Institution | Sector | Total Post-9/11 Revenue |

| University of Phoenix (Apollo)* | For-profit | $1,936,128,708 |

| Education Management Corporation (EDMC)* | For-profita | $1,131,100,076 |

| ITT Tech* | For-profit | $981,670,090 |

| DeVry University (Adtalem)* | For-profit | $928,774,463 |

| Career Education Corporation* | For-profit | $630,384,872 |

| University of Maryland Systemᵇ | Public | $546,434,790 |

| Education Corporation of America | For-profit | $495,610,842 |

| Strayer Education Inc. | For-profit | $490,445,709 |

| Universal Technical Institute Inc.* | For-profit | $398,570,667 |

| Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Inc. | Nonprofit | $366,580,569 |

a In 2017, EDMC was sold to the Dream Center, which operates the schools as nonprofit institutions.

b The University of Maryland System, which does not include the state’s community colleges, consists of 12 campuses. Seventy-two percent of the Post-9/11 revenue received by the system went to its online division—University of Maryland University College (now University of Maryland Global Campus).

* Indicates that the school was being investigated by or had settled with federal or state law enforcement agencies.

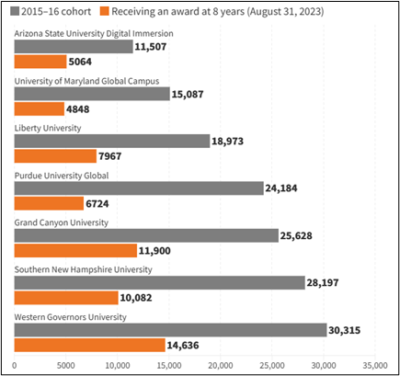

We also found that for-profit colleges receive more GI Bill funding than other sectors, as shown in Figure 2 below.[38]

Figure 2: Distribution of Total Post-9/11 Revenue by Sector, FY 2009 to FY 2017

Note: Totals exclude institutions for which “sector” was listed as unknown.

Additionally, our research found that seven of the 10 colleges receiving the most GI Bill funds in 2017 spent less than one-third of the tuition they charged VA actually educating the veterans, and they struggled with outcomes: Less than 28% of their students completed a degree, and only half earned more than a high school graduate, as shown below in Table 2.[39]

Table 2: Schools That Received the Most GI Bill Funds FY2009-2017, Percentage of Gross Tuition and Fees Spent on Student Instruction

| Institution | Type | Sector | Total GI Bill Tuition and Fees 2009-17 | Total GI Bill Tuition and Fees 2017 | Percentage of Gross Tuition and Fees Spent on Instruction in 2017 |

| University of Phoenix | Bachelor’s | For-profit | $1,936,128,708 | $192,463,300 | 15.30% |

| DeVry University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | $776,840,792 | $68,988,234 | 12.40% |

| Strayer University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | $490,445,709 | $57,056,521 | 10.90% |

| Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University | Bachelor’s | Private, nonprofit | $366,580,569 | $44,658,536 | 41.40% |

| University Of Maryland University College | Bachelor’s | Public | $359,982,581 | $63,283,316 | 31.70% |

| American Public University System | Bachelor’s | For-profit | $336,197,612 | $58,764,091 | 23.10% |

| ECPI University | Associate’s | For-profit | $335,227,624 | $44,440,711 | 38.30% |

| Colorado Technical University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | $284,479,493 | $47,958,628 | 8.20% |

| Full Sail University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | $276,845,143 | $43,744,000 | 24.70% |

| Pennsylvania State University | Bachelor’s | Public | $257,127,833 | $38,337,031 | 70.10% |

Predictably, these colleges have abysmal student outcomes.[40] As shown in Table 3 below,[41] the percentage of students who later earn more than a high school graduate is closely tied to the percent of tuition and fees that the institution spends on instruction.

Table 3: Schools That Received the Most GI Bill Funds FY 2009-2017, Percentage of Students Graduating and Earning More Than the Average High School Graduate

| Institution | Type | Sector | Completion Rate Within 8 Years | Percentage of Students Earning More Than the Avg. HS Graduate | Percentage of Gross Tuition and Fees Spent on Instruction in 2017 |

| Pennsylvania State University | Bachelor’s | Public | 68.40% | 70.20% | 70.10% |

| Full Sail University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | 54.70% | 52.30% | 24.70% |

| ECPI University | Associate’s | For-profit | 52.30% | 52.30% | 38.30% |

| Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University | Bachelor’s | Private, nonprofit | 41.80% | 77.00% | 41.40% |

| University of Phoenix | Bachelor’s | For-profit | 29.00% | 50.80% | 15.30% |

| Colorado Technical University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | 27.50% | 49.80% | 8.20% |

| University Of Maryland University College | Bachelor’s | Public | 25.80% | 70.70% | 31.70% |

| American Public University System | Bachelor’s | For-profit | 23.60% | 70.10% | 23.10% |

| DeVry University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | 22.10% | 57.90% | 12.40% |

| Strayer University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | 17.90% | 59.00% | 10.90% |

Further, approximately 100 colleges spent less than 20% of the tuition they charged VA on education costs for veterans, as shown in Table 4 below.[42] These 107 colleges charged VA a total of $703 million in GI Bill tuition and fees in 2017 alone, but siphoned off $562 million in GI Bill money for non-instructional costs or overhead, including private jets and fancy cars for their executives.

Table 4: Bottom of the Barrel Schools: Schools that Spent Less Than 10% of Gross Tuition and Fee Revenue on Student Instruction

| Institution | Type | Sector | Total GI Bill Tuition and Fees 2009-17 | Total GI Bill Tuition and Fees 2017 | Percentage of Gross Tuition and Fees Spent on Instruction in 2017 |

| Colorado Technical University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | $284,479,493 | $47,958,628 | 8.20% |

| American InterContinental University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | $171,843,483 | $17,046,392 | 9.40% |

| Capella University | Bachelor’s | For-profit | $126,111,055 | $17,656,734 | 9.40% |

| ABCO Technology | Certificate | For-profit | $757,444 | $256,425 | 6.40% |

In other words, bad actors are wasting GI Bill funding and defrauding VA and veterans. There are thousands of excellent colleges in America, and very few bad actors – yet they dominate the GI Bill funds.

VA’s Quality Controls are Inadequate

Why were obvious scam colleges approved for GI Bill in the first place? Some examples are significant. We start with the scandals of FastTrain College and Retail Ready Career Center.[43],[44] Both schools proved to be a significant waste of taxpayer money, even before the FBI stepped in.

In the case of FastTrain College, the school was raided by the FBI and ordered to pay more than $20 million for “having defrauded the U.S. Department of Education (ED) by submitting falsified documents to obtain federal student aid funds in connection with ineligible students.”[45],[46]

Even worse, Retail Ready Career Center ran a scam offering a 6-week HVAC training for veterans while also subjecting them to abusive practices, including taking their housing allowance and making them live in a substandard [disgusting] motel.[47] The owner falsely claimed, “We have the highest success rate of any other GI Bill program out there,” but the FBI and DOJ found differently.[48] The owner of Retail Ready was eventually sentenced to more than 19 years in jail and ordered to forfeit $72 million of VA benefits to the federal government for lying to gain approval to enroll veterans; DOJ eventually recouped more than $150 million from the school.[49] According to DOJ, the owner had spent veterans’ GI Bill funds on a Lamborghini, a Ferrari, a Bentley, two Mercedes Benzes, a BMW, and real estate worth $2.5 million, among other purchases.[50]

Sadly, these are not isolated occurrences. More recently, in 2020, the owner of Blue Star Learning was sent to prison for 45 months and ordered to repay VA $30 million for his fraudulent GI Bill program with falsified job placements.[51]

In 2022, the California Technical Academy was exposed for a scheme that involved over $100 million, the most significant case of GI Bill fraud prosecuted by DOJ.[52], [53] Unfortunately, so many predatory actors continue to reap the benefits veterans earned.

Just over a year ago, DOJ seized the bank accounts of the House of Prayer Christian Church – a purported “bible school” that we, at Veterans Education Success, first exposed and brought to VA’s attention, as both students and teachers had come to us to report that veterans were being blatantly cheated out of their GI Bill and abused by an alleged cult leader.[54], [55]

We presented the facts and whistleblowers to VA, but it continued to send GI Bill to the school for two more years, including for a full three months after the FBI had raided the schools’ campuses nationwide.

As recently as January 2025, the VA OIG announced charges against an “owner of a non-college-degree school and its certifying official [who] conspired to submit fraudulent information to conceal the entity’s noncompliance with the rules and regulations of the Post-9/11 GI Bill program,” taking more than $17.8 million from VA.[56]

VA’s quality controls are inadequate – similar to Title IV. The statutes governing program approval in the GI Bill are seriously outdated, even referencing classes taught “by radio,” and they continue to allow a low standard of entry.[57] Specifically:

- 38 U.S.C. § 3672 has almost no requirements. It also incorporates, by reference, the program approval requirements of Chapters 34 and 35, but those are also minimally effectual; they only forbid, for example, bartending and personality development courses, and they restrict “radio” courses, which indicates an out-of-date statutory framework.

- 38 U.S.C. § 3675 (approval of accredited courses) relies heavily on the school’s accreditation, but some accreditors offer no meaningful quality control, such as the now-defunct ACICS, which accredited ITT Tech and Corinthian Colleges.

- 3675(b) also requires that the school meet the criteria in paragraphs (1), (2), (3), (14), and (15) of 38 U.S.C. § 3676(c). While 38 U.S.C. § 3676 (approval of nonaccredited courses) has more restrictions, many are undefined, including no definition of “quality” in (c)(1); no definition of teacher “qualifications” in (c)(4); no definition of “financially sound” in (c)(9) (which could easily be defined by reference to U.S. Department of Education standards); an inadequate ban on deceptive advertising in (c)(10) (which should be clarified to ban any school that has faced legal or regulatory concerns over its advertising in the prior 5 years); and no definition of “good character” in (c)(12) (which should be clarified to ban administrators and teachers who have faced legal or regulatory action or any action by a licensing board).

Student Complaints about Quality

Complaints from student veterans attending GI Bill-approved programs continue to underscore the fact that subpar programs are failing to deliver (and we received 604 veteran complaints last year):

- Veteran DT: “I graduated from [my GI Bill-approved college] after 5 years, and in all that time, I never had a real-time conversation or interaction with a single teacher, not in a group or one-on-one. The way the courses were taught was totally ineffective. We would be assigned a bunch of stuff to read, and we were required to provide just two comments on an online discussion board. Occasionally, we were given assignments to complete, but the teachers never gave us feedback on the assignments.”[58]

- Veteran AY: “Much of the curriculum was so outdated it might as well have been from the Stone Age. We were initially taught using the Unity and Visual Studios systems. Later, when the courses switched to modern programs … they did nothing to teach us how to use them. … I often was better off learning through tutoring, Google searches, and YouTube videos than I was following the actual instruction from its online courses. To make matters worse, the terminology and policies changed drastically from one class to another, creating confusion and hampering the learning experience. It was difficult to learn basic concepts and build upon them effectively.”[59]

- Veteran AD: “I was accepted into the VRRAP program and set up to meet with [my GI Bill-approved college] to enroll in their Dental Hygiene program… Instructors are incompetent and inexperienced, Labs and course material are not taught, and I have to pay for a book payment plan for books costing 750 dollars that I can get on Amazon for less than 250 dollars. …. I was on the president’s list and dean’s list for the terms I have completed, but I haven’t even seen a dental dam or sterilized one piece of equipment. I am not learning any material and students are given answers to the quizzes and exams to keep them passing. Soon I have to let these students practice on me as part of the curriculum, but even our CPR AHA class was taught at a 22-student to 1-instructor ratio, so none of us are legally certified.”[60]

Veterans’ complaints are mirrored by the complaints from the larger student population. The Federal Student Aid (FSA) Fiscal Year 2024 Annual Report highlighted the schools that received the most student complaints, as shown in Figure 3 below:[61]

“Students who attended for-profit schools disproportionately submitted complaints about their schools relative to the share of Title IV aid funds disbursed to those schools. The for-profit sector accounts for 13% of annual aid volume but represents a quarter (25%) of FSA’s identified complaints… FSA also received a disproportionate number of complaints from predominantly online schools. FSA received 2,764 complaints (23%) about schools where more than 80% of students are enrolled exclusively online. In contrast, these schools accounted for only 9% of enrollment in Title IV-eligible schools during the 2023-24 school year…”[62]

Figure 3. Number of Complaints by School from Top 21 by Volume

Many of these schools are known for recruiting veterans and their families.

B. Individual Preparation matters

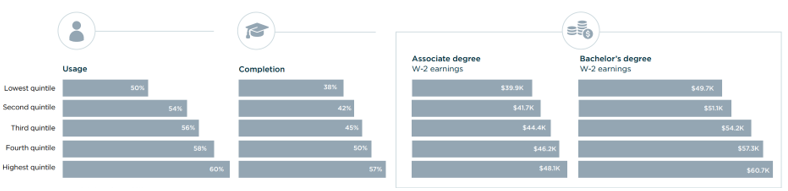

Although the GI Bill essentially represents a fully-packed “free college” for veterans, roughly half of eligible veterans do not personally use it and 38% neither personally use it nor transfer it to their kids. The Census Bureau study explored why.

Individual preparation does matter in a veteran’s decision to use his or her benefits and in his or her educational outcomes: One of the key findings from the Census Bureau study was a very strong correlation between AFQT score (representing academic preparation and skills at the time of enlistment in the military, a test administered to every single entering service member) and college enrollment, completion, and earnings. In short, the higher the AFQT score, the more likely a veteran was to use their GI Bill, graduate from college, and have higher earnings, as shown in Figure 4 below.[63]

Figure 4. Post-9/11 GI Bill-Eligible Enlisted Veterans’ Outcomes by Armed Forces Qualification Test Score (in Quintiles)

Specifically, veterans in lower AFQT quintiles were more likely to be Nonusers (i.e., were less likely to use their GI Bill benefits) than those in higher quintiles.[64] A regression analysis suggested that other veteran characteristics did not explain this gap.[65] In fact, after accounting for a wide array of veterans’ demographic and military characteristics (including military rank and military occupation), the gap between the lowest and highest quintile increased, suggesting a clear correlation between lower AFQT scores and nonuse of GI Bill.[66] A 10 point gap in usage of GI Bill between the lowest and highest AFQT score quintiles remained true during regression analyses to hold constant other demographic and military characteristics, suggesting that the other veteran characteristics included explain only a small portion of the overall gap in usage observed by AFQT and that higher AFQT scores are associated with higher GI Bill usage.[67]

Veterans’ college completion rates increased significantly with veterans’ AFQT quintile. The research showed a 19-percentage-point gap in completion between the lowest and highest AFQT quintiles – even larger than the 10-percentage point gap noted above for GI Bill usage by AFQT quintile.[68] Accounting for other veteran characteristics, this 19-percentage-point completion gap shifted to 14 percentage points.[69] This change of five percentage points suggests that the other veteran characteristics included explain only a small portion of the difference in completion between the lowest and highest AFQT quintiles. In short, higher AFQT scores are associated with higher completion rates.[70]

Earnings also correlated with AFQT score – although the gaps shrank significantly in a regression analysis: W-2 earnings for GI Bill-Clearinghouse Users who completed an associate degree or a bachelor’s degree again varied by AFQT.[71] For both associates and bachelor’s degree completers, earnings increased with veterans’ AFQT quintile.[72] The earnings gap between the lowest and highest AFQT score quintiles spanned about $8,200 for associate degree recipients and $11,000 for bachelor’s degree recipients.[73] However, after accounting for other veteran characteristics, the earnings gap shrunk to $2,500 for associate degree recipients and $5,100 for bachelor’s degree recipients – suggesting that demographic differences and differences in military occupation and rank play at least some factor in the gap in earnings.[74]

In short, individual preparation matters. In the GI Bill experience, the best outcomes strongly correlate with veterans who entered the military with higher scores on a test examining academic preparation and aptitude.

C. Guidance and Pathways Matter

The third lesson for Title IV from the GI Bill is that guidance and pathways matter.

Some Veterans are Not Using Their GI Bill

As the Census Bureau study found, many veterans are simply not even using their GI Bill. The research showed that nearly 2 in 5 veterans did not use their GI Bill.[75]

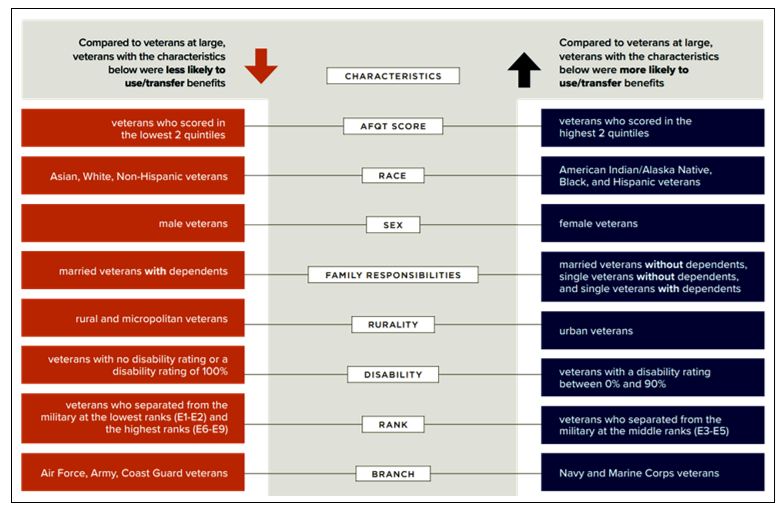

GI Bill usage varies significantly by which branch of the military a veteran has served in – and this suggests strongly that guidance matters. Specifically, as shown in Figure 5 below, Air Force veterans were most likely to forgo GI Bill benefits (45%), followed by veterans from the Army (41%) and Coast Guard (39%), while those in the Navy and Marine Corps were least likely to be nonusers, at 32% and 30%, respectively.[76] Gaps between Air Force veterans and veterans from other branches generally shrank after the research team ran a regression analysis to account for other characteristics, although the gap did not shrink between Air Force and Coast Guard veterans. Overall, it appears that different branches of the military have different usage rates, suggesting they may be receiving different guidance messages either in the military or as they are exiting (during the exit process, when service members are given extensive guidance).

In terms of demographic groups, as shown in Figure 5 below, nonuse consistently increased with age and was highest for veterans who separated from the military at older ages – 55 to 65 (82%).[77] This may make sense because their potentially greater years of military experience and potentially fewer years planned in the civilian labor force may make them less inclined to view their personal use of GI Bill benefits as needed or advantageous.[78]

Nonuse was lowest (in other words, use of GI Bill was highest) for those who left the military with a midlevel rank of E-4 or had a VA disability rating of 10% to 20% (27%).[79]

Figure 5. Snapshot of Post-9/11 GI Bill-Eligible Veterans’ Benefit Use

Rural and micropolitan areas were also less likely to use the GI Bill.[80] And non-married veterans were less likely to complete a degree and earn more.[81]

Veterans who did not use their GI Bill were earning less, and the earnings gap was larger for female veterans, American Indian/Alaska Native veterans, and Black veterans:[82]

- Female veterans were significantly more likely than male veterans to use Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits and to earn a degree. Still, they earned significantly less than male veterans with the same degree. However, the earnings gap by sex was smaller for veterans than for the general population.[83]

- Racial and ethnic groups that have been historically underrepresented in higher education were more likely to use Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits to enroll in postsecondary education. This may be due, in part, to targeted recruiting by for-profit colleges who seek out vulnerable racial minorities. In addition, the usage gap diminished between Hispanic and non-Hispanic veterans during a regression analysis and disappeared entirely between white and Native veterans, suggesting that other factors were at play.[84]

- Racial and ethnic underrepresented groups were less likely to earn a degree within six years than veterans overall. Black veterans’ earnings were significantly lower than other veterans, and American Indian/Alaska Native earnings were also lower. Still, the earnings gaps for these racial subgroups were smaller for veterans than for the general population.[85]

The top reasons that veterans cited for not using their GI Bill benefits were as follows: A lack of information, specifically around the expiration date and transfer requirements, was the most frequently mentioned reason that veterans shared for not using their benefits.[86] Specifically, many nonparticipants were unaware that, if they wanted to transfer their GI Bill to a dependent, they needed to have completed that transfer while still on active duty.[87]

Other veterans reported they were purposefully delaying their use of the GI Bill in order to maximize its benefits, such as paying out of pocket for community college in order to “save” their GI Bill for more expensive degrees they hoped to achieve later. Still others found the housing allowance insufficient, and others struggled to secure VA home loans as lenders did not count GI Bill benefits as income.

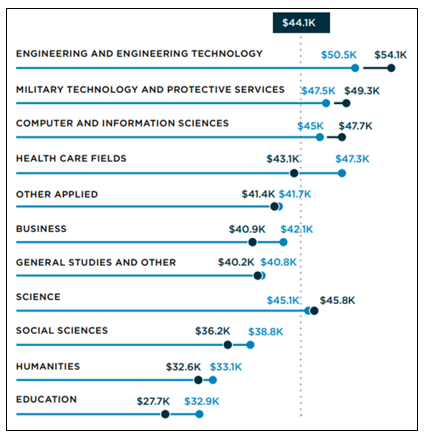

Graduation rates and earnings also differ by the specific type of degree and field of study that is pursued.[88] And this suggests, again, that guidance is needed to help veterans select a path with the best possible outcome.

As shown in Figures 6 and 7 below, the interagency research team at the Census Bureau found that veterans’ earnings after using their GI Bill increased with certain fields of study, while it decreased with other fields of study – and this was true at both the associate and bachelor’s degree levels.

Among associate degree completers, as shown in Figure 6, the interagency research team at the Census Bureau found that those who majored in engineering or military technology and protective services had mean earnings more than 10% above the overall average (in fact, 23% and 12% above, respectively).[89] Those with majors in computer science, health care fields, other applied fields, business, and science all had earnings within 10% of the overall average, while social sciences, humanities, and education majors had earnings that were more than 10% lower than the average (18%, 26%, and 37% lower, respectively).[90]

During a regression analysis to explore whether some of the variation in earnings by major among associate degree completers can be explained by veterans’ academic preparedness as measured by their AFQT scores, demographic characteristics (e.g., age), and military experiences (e.g., military occupation and rank at separation), the interagency research team at the Census Bureau found that the variation by major shrank.[91] Most notably, computer science, military technology and protective services, and engineering and engineering technology majors, the three highest earning majors, all declined by over $1,500, suggesting that other factors may be playing a role in these majors’ earnings.[92] Education, health, and social science majors, on the other hand, earn over $2,500 more than they did before accounting for other characteristics (though education and social sciences majors still earn less than the average associate degree recipient).[93] Overall, the results indicate that a veteran’s field of study is related to associate degree recipients’ later earnings, even controlling for other factors like military rank.[94]

Figure 6. Fields of Study: Associate Degree W-2 Earnings for Adjusted and Mean[95]

The interagency research team at the Census Bureau found that the earnings of bachelor’s degree recipients varied by field of study, too, but with some differences from what was observed for associate degree recipients, as shown in Figure 7.[96] Among bachelor’s degree recipients, the interagency research team at the Census Bureau found that computer science majors and engineering majors earned more than 25% above the average, earning 28% and 32% above the average, respectively.[97] Military technology and protective services majors this time joined majors in health care fields and business majors to have earnings very close to the average for all GI Bill Clearinghouse Users that received bachelor’s degrees.[98]

As with associate degree recipients, bachelor’s degree recipients who completed social science, humanities, and education majors had earnings more than 10% below the average for bachelor’s degree recipients; however, in contrast to associate degree completers, bachelor’s degree completers who majored in science also had earnings more than 10% below the average.[99]

During a regression analysis to account for veterans’ other characteristics, the interagency research team at the Census Bureau found that the variation by major again shrank, with two groups having the most notable changes.[100] The research team observed declines of $4,100 for computer and information science and $5,000 for engineering and engineering technology, and a bachelor’s degree in a health care field increased from $100 to $5,300 above average.[101] This suggests that majoring in health could be leading to higher salaries for veteran groups that are otherwise earning less.[102] Overall, these results indicate that the wage differences observed for veterans with different majors may be shaped by the characteristics of veterans pursuing these majors as well.[103]

Figure 7. Fields of Study: Bachelor’s Degree W-2 Earnings for Adjusted and Mean[104]

Guidance is Also Needed to Protect Veterans from Deceptive Recruiting that Leads Them to Enroll in the Worst Quality Programs

Too many veterans report feeling railroaded into the lowest quality, predatory postsecondary programs. How is it that so many of the worst quality postsecondary programs are receiving the most GI Bill funds? And how is it that so many veterans feel they were deceived and duped by aggressive salesmen from postsecondary programs?

Whistleblowers and veterans alike have reported vastly deceptive recruiting practices by salesmen for for-profit programs who, themselves, report operating in “boiler room” environments where they are under constant pressure to increase student enrollments “by any means necessary” – which was also well-documented during the two-year investigation by the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions.[105]

As then-President Barack Obama explained in signing Executive Order 13607 (April 2012):

“It’s not that easy…. You go online to try and find the best school for military members…. You end up on a website that looks official. They ask you for your email, they ask you for your phone number. They promise to link you up with a program that fits your goals. Almost immediately after you’ve typed in all that information, your phone starts ringing…. But, as some of your comrades have discovered, sometimes you’re dealing with folks who aren’t interested in helping you. They’re not interested in helping you find the best program. They are interested in getting the money. They don’t care about you; they care about the cash. So they harass you into making a quick decision with all those calls and emails…. I’m not talking about all schools…. But there are some bad actors out there. They’ll say you don’t have to pay a dime for your degree but, once you register, they’ll suddenly make you sign up for a high interest student loan. They’ll say that if you transfer schools, you can transfer credits. But when you try to actually do that, you suddenly find out that you can’t. They’ll say they’ve got a job placement program when, in fact, they don’t. It’s not right. They’re trying to swindle and hoodwink you.”

How aggressive is the recruiting? A veteran and staff member at VFW tested the system. He told National Public Radio, “Within three to four days, I got in excess of 70 phone calls and I got well over 300 emails” from for-profit colleges.[106]

For-profit college salesmen continue to recruit on military bases and VA hospitals. A whistleblower from DeVry told us that, because of a cozy relationship with a military base commander, DeVry recruiters were given the opportunity to recruit servicemembers during mandatory sessions during duty hours.[107]

Earlier, as Business Week reported, Ashford University even signed up a Marine with a traumatic brain injury convalescing in a military hospital: “U.S. Marine Corporal James Long knows he’s enrolled at Ashford University. He just can’t remember what course he’s taking.”[108]

The U.S. General Accounting Office ran two undercover investigations, sending undercover agents to pose as students. Every single one of 15 large for-profit colleges deceived federal undercover officers about the quality of education, cost, and likely job and salary for graduates.[109] Four colleges engaged in actual illegal fraud (such as directing students to falsify federal student loan applications). The undercover officers then registered as students at those colleges, and found the “education” of such low quality that students were encouraged to cheat and received top grades for submitting photos of celebrities in lieu of a required essay.[110]

How deceptive is the recruiting? Education salesmen turned whistleblowers have explained what is going on inside the massive call centers where for-profit college salesmen are under constant pressure to sign up veterans:

- “We’re selling you that you’re gonna have a 95 percent chance that you are gonna have a job paying $35,000 to $40,000 a year by the time they are done in 18 months,” Brooks College (Career Education Corporation) salesman Eric Shannon told CBS’ 60 Minutes. “We later found out it’s not true at all.”[111]

- DeVry University instructed its salesmen to “get asses in classes” through “the military gravy train,” even if service members are not ready or are being deployed to heavy fighting zones, according to Christopher Neiweem, a veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom and DeVry salesman, who was assigned specifically to target military students.[112] Neiweem told Congress he was instructed to pose as a “military advisor” affiliated with the Pentagon. Following his testimony, four additional DeVry military salesmen wrote Congress to say they were told to do the same.[113]

- “You’d probe to find a weakness,” said Brian Klein, a former admissions employee at Argosy University Online, one of four major colleges operated by EDMC. Argosy’s recruiters filed a whistleblower lawsuit against EDMC, which the U.S. Department of Justice joined on behalf of deceived students and taxpayers. “You basically take all that failure and all those bad decisions, and you spin it around and put it right back in their face as guilt, to go to this shitty university and run up all of this debt.”[114]

- “Everything here is about the numbers. You make your numbers, or you are out of a job,” recruiters at Colorado Technical University – housed in an office building with no classrooms and no professors, but row upon row of salesmen – told the New York Times.[115] Salesmen from Ashford reported the same.[116]

Internal recruiting documents of predatory for-profit colleges – made public during the two-year investigation by the U.S. Senate Education Committee – reveal that many for-profit colleges engage in pain-based recruiting.[117] Salesmen are specifically taught to emotionally manipulate veterans into signing up, because, as their internal corporate documents acknowledge, students are unlikely to make a “rational” decision to attend for-profit colleges, given that community colleges and public universities offer lower cost, higher quality, accredited degrees.[118]

V. Insights for Title IV from GI Bill Outcomes

For decades, a central tenet of advocacy for broad college access has been the elimination of financial barriers. The GI Bill, providing up to four academic years of full tuition and fees, as well as housing and books allowances, represents an idealized model for college financing – removing from students any financial strain in order to enable their best student outcomes and later financial success as members of the civilian workforce. Therefore, the lessons we learn from the GI Bill can shed light on the larger idea of free college as well as overall Title IV financing and structure.

As we have seen in this review of GI Bill outcomes, institutional quality, the individual student’s academic preparation, and professional counseling and guidance are critical elements for optimal outcomes. This may sound intuitive, but the GI Bill data from the Census Bureau interagency team incontrovertibly demonstrate the veracity of that intuition. These three overarching components for student success, furthermore, apply with equal force to all variants of federal policy in support of broader access to higher education. They would play as central a role in the success or failure of any configuration of a free college scheme as they already do in the current federal student aid system.

Like the GI Bill, Title IV has long suffered a massive and costly blindspot on the issue of quality. Massive amounts of scarce aid dollars are funneled into low-quality, predatory institutions, including online college chains providing little education, that regard Title IV as little more than an indirect form of corporate welfare. Especially at a time when resources are under the greatest stress due to efforts to cut costs, it is critical that we redirect federal policy in the direction of extracting the best outcomes from every aid dollar through insistence on quality. The long history of lessons about predatory institutions targeting the GI Bill (which predate Title IV) should be ample evidence of the need to address this longstanding problem in both Title IV and the GI Bill. Data from the interagency research team at the Census Bureau, which utilized a population set of 2.7 million veterans to draw clear conclusions, make clear that outcomes are worse at for-profit colleges and at colleges that spend the least on instruction.

Failing a comprehensive overhaul of current gatekeeping and oversight mechanisms in federal student aid, two comparatively simple but potent policy instruments to control for quality in higher education are reasonable instructional spending requirements and properly designed institutional risk-sharing for student loan defaults.

As indicated in the discussion of the GI Bill above, instructional spending is strongly correlated with higher completion rates and higher post-enrollment earnings, and this held true in the Census Bureau research across sex, race, rurality, and military rank, as well as overall among all veterans.[119] Although the interagency research team at the Census Bureau was careful to specify that they could not show causation without a randomized control trial in which some veterans were randomly assigned GI Bill and others randomly were not (which would be immoral), the team did take note of strong correlations, as it did in the case of instructional spending. In short, the interagency research team at the Census Bureau found a very strong correlation between an institution’s instructional spending and its student outcomes, including earnings, and this held true even when accounting for a wide range of military and demographic characteristics in a regression analysis.

Instructional spending, therefore, should be viewed as one clear answer for improving student outcomes. Instructional spending at American colleges is also easier to track than many other inputs into student success, given that every American college, every year, reports its revenue and spending categories to the U.S. Department of Education in the IPEDS Finance Survey. Finally, instructional spending is easier to require and enforce than other inputs into student success, because it is so cleanly and simply measured. Federal policymakers should consider imposing a floor on the portion of a college’s tuition and fees that must be spent on the substance of students’ education – as opposed to spending on the institution’s advertising, marketing, amenities, or executive perks. Requiring such a floor would ensure that at least some portion of tuition dollars financed with federal aid is actually used to teach students.

Similarly, in the GI Bill context, where colleges are allowed to charge VA tuition for each veteran the colleges enroll, it is especially incumbent on federal policymakers to ensure that colleges are not overcharging VA by failing to spend those dollars on the veteran in whose name the institution is charging VA.

In addition, the enormous variances in higher education quality are largely to blame for one of U.S. higher education’s greatest structural inefficiencies: portability and transfer of academic credit. The most frequent problem cited by veterans is that they learn only too late – after having used their benefits at a low-quality, but nevertheless accredited, school – that none of the credits they have earned are transferable. That there are eligible institutions whose credits are universally rejected by other eligible schools is compelling evidence that the government is setting the bar on quality too low, a fact that is, sadly, easy to see in hindsight through numerous cases of schools such as ITT Tech, Corinthian, and Argosy, among others.

Even when schools are not engaged in outright fraud, enormous differences in curriculum, instruction, and assessment – and the lack of transparency about what is actually being taught – create a huge unpredictability as to whether credits earned in one institution will count toward earning a degree at a different institution. While some of the credit denials are due to unreasonable institutional policies, much of it is due to the highly uneven quality and rigor of courses offered by various institutions, despite the fact that they are all eligible for federal subsidies. Raising the bar on academic quality through a minimum requirement on instructional spending would go a long way toward addressing some of the transfer issues that sidetrack or derail many nontraditional students.

Turning from front-end gatekeeping to ensure minimal success in student outcomes, we now examine post facto incentives to ensure institutions are invested in student success. With instructional spending serving as an upfront quality mechanism, institutional risk-sharing in student loan losses could then work as a post facto incentive in promoting acceptable repayment outcomes. It is certainly true that students bear a certain degree of responsibility for their choices in higher education. Their choice of majors, whether they study diligently, and their life habits influence their odds of graduation and their post-enrollment earnings. But while they do bear individual responsibility for their decisions, academic and economic outcomes are not entirely under their control. Life events beyond their control – such as illness, disability, disasters, a death in the family, or loss of employment – can derail students.

But an even more powerful contributing factor to students’ educational outcomes are the institutions they attend. The very act of admitting students into programs financed with student loans imposes a duty of care about the students’ future financial circumstances that institutions have historically shrugged off. Federal student loans are, in fact, no different than grant money insofar as the schools are concerned, because they face no liability for the adverse outcomes of borrowing that could be reasonably attributed to them.

Financing known low-wage academic fields[120] with student loans may make sense to a young person hoping that he or she will be the exception to the abysmal future earnings data for that field of study, but institutions that knowingly recruit students into such programs should be required to share in the repayment pain that solely falls on their former students.[121]

The GI Bill also teaches us that an individual student’s preparation and guidance are critical to his or her academic success, Recall that the interagency research team at the Census Bureau found one of the strongest correlations between a veteran’s AFQT score (representing his or her academic preparation and skills at the time of enlistment into the military) and his or her later usage of the GI Bill, college completion, and earnings. The interagency research team also found that GI Bill usage differed depending on which military branch the veteran served in– where he or she received mandatory guidance both during military service and during the exit process of separation from the military. Recall that the interagency research team at the Census Bureau found that Air Force veterans were the most likely to forgo GI Bill benefits (45%), followed by veterans from the Army (41%) and Coast Guard (39%), while those in the Navy and Marine Corps were least likely to be nonusers, at 32% and 30%, respectively. In short, while only 30% of Marines failed to utilize their GI Bill upon leaving the military, 45% of Air Force veterans did so.

Sadly, the federal government has had an uneven record on both preparing students for higher education and guiding them in their college pathway, primarily because of the federal government’s limited jurisdiction and authority in K-12 education. The federal government has launched multiple lofty but unsuccessful initiatives such as Goals 2000, No Child Left Behind, and Race to the Top over the decades – with little effect.[122] Credible higher education policy cannot, however, merely bemoan the reality that too many aided students enroll in postsecondary programs unprepared: it should devise a policy response. That policy response has historically taken the form of the TRIO programs[123] and the GEAR-UP program.[124] Significantly increased funding and expansion of these programs would be the most immediate partial remedies already available under current law to address the need for students to be better prepared for college and better guided – two strong findings of fact about the GI Bill from the interagency research team at the Census Bureau.

Additional policy thought should also be given to the creation of pre-collegiate remedial high school programs for eligible students (to be supported by both the federal and state governments). Financing significant remedial education (as opposed to a few courses) with Title IV student aid is one of the most problematic practices in higher education, since it, in effect, charges college-level tuition for secondary education that students were entitled to receive for free. Serving students with significant remediation needs in free non-collegiate environments (“remedial high schools”) would help them attain the academic skills they need without absorbing the full-on costs of college coursework.

Finally, it is worth considering that the general conditions of the macroeconomy play a much larger part in outcomes than advocates may realize. For decades, it has been an article of faith among many higher education advocates that college is the entry card into middle-class status. This belief is founded on the post-War experience of the returning GIs, many of whom could not have dreamed of college before the GI Bill, whose diplomas did indeed open doors for the veterans and led to the greatest expansion of economic opportunity in the nation’s history. Today, however, while it is certainly true that college graduates tend to have about half the unemployment rate of non-college graduates,[125] a college degree no longer guarantees a middle-class lifestyle like it once did. This is due to the larger dynamics of growing economic inequality and stagnant wages at a time of increased costs,[126] as well as the sizable student loan debt-service obligations most college graduates carry, which many students find extremely burdensome and which became a rallying cry of student advocates prior to and during the Biden Administration, leading to political pressure on the Biden Administration to cancel student loan debt.

The GI Bill data from the Census Bureau study confirm other macrotrends as well. These include stubborn patterns of income disparity based on race and gender, as well as significant variances in economic outcomes based on field of study. While some of the structural issues, such as possible discrimination or lingering effects of past discrimination in the labor market, may not be directly addressable through higher education policy, differences in outcomes by field of study may require consideration of new policy refinements, such as differential pricing and/or differential subsidies, perhaps along with enrollments caps.

In conclusion, the comprehensive analysis of the GI Bill’s outcomes performed by the interagency research team at the Census Bureau provides a number of definitive conclusions that should inform efforts to reform Title IV programs. Implementing instructional spending requirements, institutional risk-sharing, expanded college preparatory programs, and improved guidance could create a more equitable and effective system. These reforms would ensure that federal education dollars serve their intended purpose: providing genuine opportunity for upward mobility, rather than perpetuating a cycle of debt and unrealized potential. The data clearly demonstrate that quality matters — in institutions, in preparation, and in guidance. If we are truly committed to education as a pathway to economic security and social mobility, then we must design policies that prioritize these elements and hold institutions accountable for delivering them. Only then can we fulfill the promise of higher education as an engine of opportunity for all Americans, regardless of background, in a changing economic landscape that demands nothing less.

[1] See CUNY Digital History Archive, https://cdha.cuny.edu/coverage/coverage/show/id/33

[2] Nations, Jennifer M., “How Austerity Politics Led to Tuition Charges at the University of California and City University of New York.” History of Education Quarterly, Volume 61, Issue 3, August 2021, pp. 273-296.

[3] Gladieux, Lawrence E., and Thomas R. Wolanin. Congress and the Colleges: The National Politics of Higher Education. Lexington Books, 1976.

[4] Basaldua, Fructoso. “Connecting Disinvestment in Public Higher Education, Rising Tuition, and Student Debt.” Footnote: The American Sociological Association Magazine, Volume 51, Issue 2, 2024.

[5] Mishel, Lawrence, Gould, E., and Bivens, J. “Wage Stagnation in Nine Charts.” Economic Policy Institute, 2015. Real wages have increased since the mid-2010s but in unequal patterns for different income levels.

[6] Archibald, Robert B., and Feldman, D. “State Higher Education Spending and the Tax Revolt.” College of William and Mary, Department of Economics, Working paper #10, 2024

[7] “Household Debt and Credit Report: Q4 2024.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Center for Microeconomic Data. 2024.

[8] Fry, Richard, and Cilluffo, A. “5 Facts about Student Loans.” Pew Research Center, 2024.

[9] See https://studentaid.gov/data-center. Drawing definitive conclusions about the implications of below-interest payment amounts is challenging due to the multiple student loan repayment options, some of which generate affordable payment amounts below interest by design.

[10] See, e.g., Foroohar, Rana, “The US College Debt Bubble Is Becoming Dangerous,” Financial Times, April 9, 2017.

[11] Interview on file at Veterans Education Success. For privacy protection, the students’ names are withheld.

[12] Dortch, Cassandra, “GI Bills Enacted Prior to 2008 and Related Veterans’ Educational Assistance Programs: A Primer,” Congressional Research Service. Oct. 6, 2017. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R42785.pdf

[13] National Archives. “Servicemen’s Readjustment Act.” (n.d.), https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/servicemens-readjustment-act.

[14] National Archives Foundation. “G.I. Bill of Rights.” (n.d.), https://archivesfoundation.org/documents/g-i-bill-rights/

[15] Later versions of the GI Bill, including the Korean War (1952) and Vietnam War (1966) G.I. Bills, continued the program, but with gradually reduced benefits. GI Bill Extended to Korea Veterans. (1953). In CQ Almanac 1952 (8th ed., pp. 205-207). Congressional Quarterly. http://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/cqal52-1378844. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks on America, Senator Jim Webb spearheaded the creation of the Post-9/11 GI Bill for the men and women returning from Iraq – with higher education as the core element of the program.

[16] See The Century Foundation, The Cycle of Scandal at For-Profit Colleges, https://tcf.org/topics/education/the-cycle-of-scandal-at-for-profit-colleges/

[17] Id.

[18] House Select Committee to Investigate Educational, Training, and Loan Guaranty Programs Under GI Bill, Created Pursuant to H. Res. 93, 82nd Congress, 2nd Session, House Report No. 1375 (Feb. 14, 1952), https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtZzJYWnpRbVkwZE0/view?resourcekey=0-oe-j6Mjzn3D8-jrhbZfEvA

[19] Id.

[20] Radford, A., Bloomfield, A., Bailey, P., Webster, B. H. Jr., & Park, H. C., “A First Look at Post-9/11 GI Bill-Enlisted Veterans’ Outcomes” (2024), American Institutes for Research; U.S. Census Bureau; and National Center for Veterans Analysis & Statistics, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, https://vetsedsuccess.org/a-first-look-at-post-9-11-gi-bill-eligible-enlisted-veterans-outcomes/.

[21] Id.

[22] See id.

[23] Id.